In August of 2019, the first technical dive expedition for scientific research was carried out in the Galapagos. We were accompanied by Monty Halls and a film crew who wanted to capture this unique expedition, which you can see featured in the documentary “My Family and the Galapagos”. The mission was to explore and to take samples of a newly discovered deep-water kelp forest between depths of 48-70 m, which lies on top of the summit of the Bajo San Luis seamount. This has been one of the most exciting and challenging dives of my career.

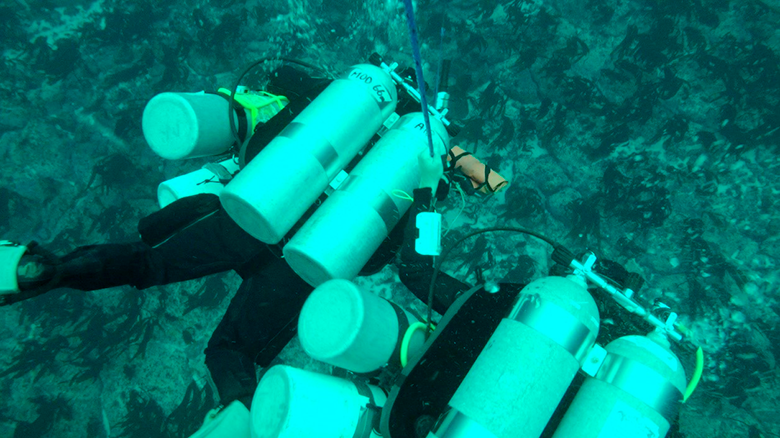

Discovered by CDF scientists from the Seamounts Research Project in November of 2018 using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV), the macro-algae forest appears to be dominated by what scientists believe is a new kelp species to the Galapagos Archipelago, and may even be new to science. Kelp are usually found in cold and shallow waters, thus finding a kelp forest in the tropics is like finding a new polar bear species living in the Sahara Desert. There are few deep-water, tropical kelp forests have been found around the world, but they remain understudied. The main reason for our dive was to collect kelp specimens for genetic analysis, take water samples and install temperature and light sensors, and to assess the environmental variables of this system.

The DIVE

The atmosphere of the team was one of nervousness as we waited for the boat to reach its destination. The technical dive team consisted of Javier, Jorge Mahauad, and myself. We all knew the entire expedition could be cancelled in a second if conditions weren’t perfect. One of the biggest concerns for the dive to go ahead was current. With a strong current, there is a danger of the divers being swept away and lost at sea. Technical dives already come with an increased risk of decompression sickness, so we did not want to take any extra chances.

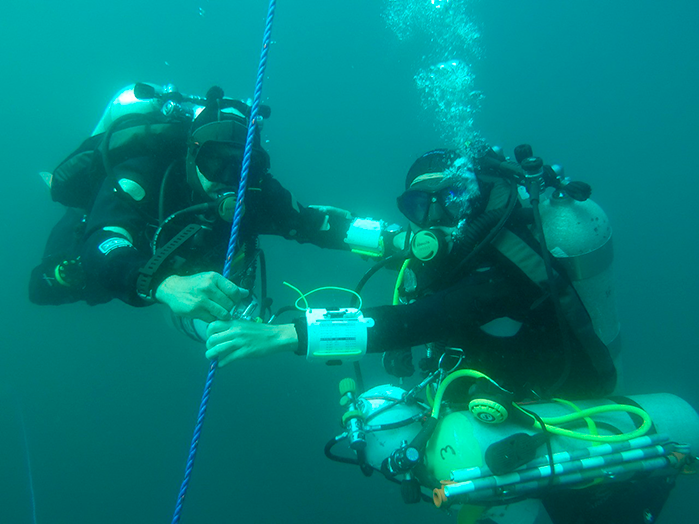

Time was of the essence, so as soon as the boat reached the site we followed our planned steps. First we assessed conditions, currents and confirmed the presence of kelp using our little ROV Trident. Then by employing a depth sounder, we located the shallowest site on the seamount summit, on which we dropped a cement-based anchor, with a line and buoy coming to surface. This line is our safety-line along which we descend and ascend. As soon as we got the green light to dive, we suited up and back-rolled off the boat and began our swim down into the twilight.

Any nerves that I had, disappeared immediately, as soon as we started the descent into the blue. This dive had months of planning, so we were as prepared as possible. At first, we descended into a large plankton bloom, making visibility limited, but at 40m the temperature dropped by 4 degrees to 15°C and the water became crystal clear. As far as the eye could see, kelp was gracefully swaying back and forth.

Monty Halls and camera man Dave Mothershaw followed us down but stayed at 30m along the descend line, ready to receive samples that we collected, and filming the entire process

“My lingering memory of this dive was hovering at 30 meters, and watching the team descend to the top of the seamount beneath me. They looked exactly like what they were, modern pioneers, landing on top of an undersea mountain peak that held a unique ecosystem. I was profoundly impressed by their professionalism and scientific rigor - I think Darwin would have been very, very happy to be part of that team.” – Monty Hall description of this experience

This dive was surreal, as well as somewhat of an emotional moment for me as it finally allowed me to be surrounded by the mysterious kelp, which I had been studying for months at my desk. With time against us, we got to work installing the sensors and collecting kelp samples. There was just enough time to take a water sample before beginning our long ascent to the surface.

By the time we hit 12 m the current was ripping. Our bubbles were being swept away horizontally and we had to firmly grip the safety line to stop us being swept away.

After safely surfacing, it was time to warm up, head back to the lab to begin preserving the precious, 1.5m long kelp and celebrate the success of the day.

What is technical diving?

Technical diving, put simply, is any diving that is set outside of recreational diving limits of 40 m. It also is defined as diving during which you are exposed to a “ceiling”, that does not allow a you to safely ascend to the surface at any moment of the dive without exposing yourself to danger. Thus, you are obligated to make certain stops during the ascent to avoid decompression sickness (a.k.a. the bends).

Imagine shaking a bottle of Coca Cola – then you open the bottle quickly, the drink will spray everywhere. But if you open it slowly, you can control the amount of bubbles being released and you don’t spill your drink. This concept is similar to decompression sickness. At depth, your tissues become loaded with nitrogen, as you ascend the nitrogen is released back into your blood streams as small gas bubbles. If you ascend too quickly, the gas bubbles can block your blood vessels, which could lead to paralysis or death.

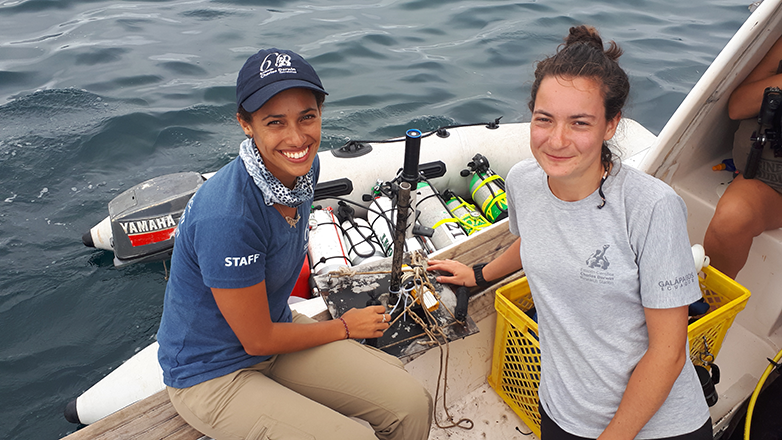

During technical dives, your body gets loaded with more even nitrogen than during recreational dives, as you are going deeper. This means you must take very long decompression stops during the assent, to allow the gas to be released slowly. However, tech divers can “cheat” by taking extra tanks with different mix of gases, that speeds up the decompression process. So, for the dives down to the kelp forest at approximately 55 m depth, we used normal air filled tanks to breathe at the bottom, but then switched to 50% oxygen and 100% oxygen blends during the ascent stops, which meant we each had to dive with four scuba tanks as opposed to the usual single tank on a recreational dive.

It comes as no surprise that technical diving requires a lot of training and experience. I had already completed many, technical dives while working with Ashley Carreiro at the NGO Marine Conservation Philippines (MCP) researching mesophotic reefs (35m-50m). This meant I had the necessary skillset to tackle these challenging dives safely.

Lead scientist Salome Buglass, mentioned “Learning that tech diving is a viable method to reach and survey these twilight ecosystems is very exciting, from only two dives we were able to collect so much valuable data, so I need to get myself certified ASAP to uncover how these kelp forests live at the edge of their light limits”

There is still much to learn about this mysterious ecosystem, specimens and data we collected on these dives, will help answer at least a few of the many questions we have. A big thank you is in need to Monty Halls and SeaDog Productions for making this pioneering expedition possible.

References

- Graham M.H., Kinlan B.P., Druehl L.D., Garske L.E. & Banks S. 2007. Deep-water kelp refugia as potential hotspots of tropical marine diversity and productivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104: 16576–16580

- Nelson, W., Duffy, C., Trnski, T. and Stewart, R., 2018. Mesophotic Ecklonia radiata (Laminariales) at Rangitāhua, Kermadec Islands, New Zealand. Phycologia, 57(5), pp.534-538.

- Marins, B.V., Amado‐Filho, G.M., Barbarino, E., Pereira‐Filho, G.H. and Longo, L.L., 2014. Seasonal changes in population structure of the tropical deep‐water kelp L aminaria abyssalis. Phycological Research, 62(1), pp.55-62.