Author: Peter Kramer

The Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF) was established in 1959, the year when the Galapagos National Park was also legally created. Both institutions were set up to protect the wildlife and conserve the ecosystems of Galapagos - the National Park as a government institution enforcing conservation laws and rules, the CDF as an international organization undertaking research and providing scientific expertise. The two institutions complement each other, and both carry out education and training programs.

But what and who was involved in the CDF started? Clearly, the two people who kicked off that process were Robert Bowman and Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt, two junior scientists who, independently of each other, they did research on birds and other wildlife on Galapagos in 1952 and 1954. Upon their return to California and Germany respectively, they both rang alarm bells, again independently of each other, in notes to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

They reported that much of the endemic Galapagos wildlife was being destroyed by direct human depredation and by introduced invasive species. They predicted that many endemic species would soon become extinct, and that the entire Galapagos ecosystem would collapse and disappear. They called for effective conservation measures and emphasized the need for a research station to be built on the Islands.

IUCN had just been set up a few years earlier by UNESCO at the initiative of its first Director General, the British biologist Julian Huxley. Bowman’s and Eibl’s warnings were heard and understood by IUCN and supported by prominent scientists in Europe, Ecuador and the US.

Up to this point, these talks about plans for a station on Galapagos remained just that: talk. Things became more serious and concrete when IUCN’s parent organization, UNESCO, was brought in. UNESCO had the financial muscle and I imagine the Ecuadorian government felt comfortable with that organization’s involvement because Ecuador had joined UNESCO right after it had been set up in 1946. So, at the request of Ecuador, UNESCO funded a three-month expedition, which later became known as the “UNESCO Mission”.

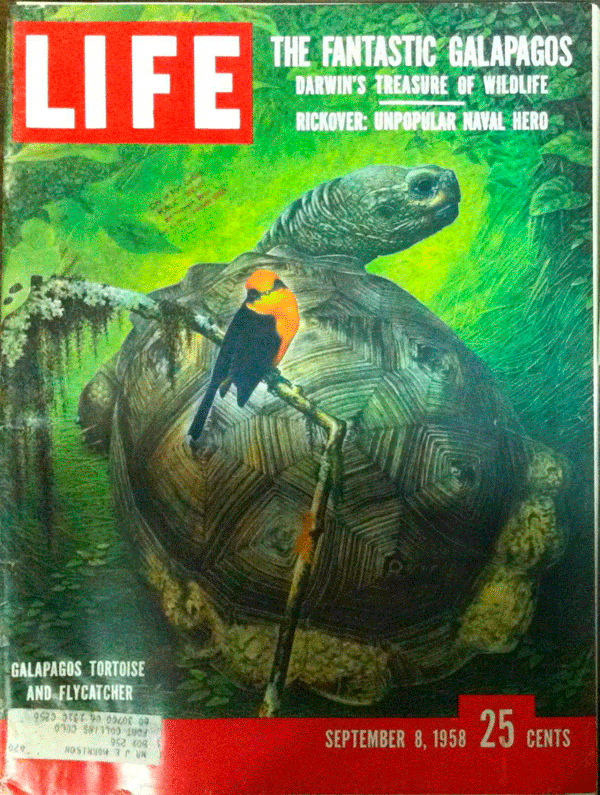

The aim of this mission was to provide more information on the status quo on Galapagos, to submit recommendations for action and to inform the wider public about the exceptional value of these islands. Eibl was appointed “UNESCO Expert” and Bowman and two LIFE Magazine journalists were added to the mission with additional funding from the US, - Bowman was included so that he “might serve as the American delegate on the UNESCO mission”, as he wrote later in his report. And the two journalists’ task was “to obtain adequate photographic documentation of the islands and their biota for publicity purposes”. These two men sent by LIFE Magazine were Alfred Eisenstaedt, a photographer, and Rudi Freund, an artist. Alfred Eisenstaedt, at the time the oldest and most distinguished of this group, is today considered one of the most accomplished photographers of the 20th century. One of his most famous photos is the snapshot of an American sailor kissing a nurse on Times Square upon his return from the war in 1945.

Thanks to logistical support by the Ecuadorian navy this mission was successful. The group was really heterogeneous, but it formed a fragile team and stuck together on Galapagos from July to November 1957. They produced significant reports describing the dire conservation situation on Galapagos, promoting better protection of the islands and pushing for the establishment of a research station. But it was not an entirely happy trip: Eisenstaedt took fabulous photos but had to leave early because he was needed elsewhere, and Bowman and Eibl-Eibesfeldt, the two scientists, did not get along at all. Later I witnessed the two of them speaking with polite condescendence about each other. They wrote separate reports to UNESCO, which didn’t contradict each other, but they differed in style and detail. Also, they never served jointly on the CDF Board. Surprisingly, though, they both concluded that the best place for the construction of a research station would be Tortuga Bay!

The resulting 1958 publication in LIFE Magazine was very impressive. Darwin and Darwinism were the themes. Neither had really been popularized in that way before in the US and Eisenstaedt’s exceptional photography and Freund’s art highlighted the special character and beauty of Galapagos. There is no doubt that this publication, together with the Sierra Club’s luxurious two-volume “Galapagos, The Flow of Wildness”, published ten years later, provided much of the publicity that helped getting nature-oriented tourism underway on Galapagos in the late 60’s and 70’s.

Eibl-Eibesfeldt’s and Bowman’s reports and their communication with scientific leaders shook up people and institutions on both sides of the Atlantic. Ornithologists were particularly engaged. Dillon Ripley and Jean Delacour, leaders of the International Council for Bird Preservation, went to Quito, discussed the plans for a research station with government officials and were encouraged.

All that happened as 1958 approached, the centenary of the publication of Darwin’s and Wallace’s works on the evolution theory. And it actually was during that centennial year that determining decisions regarding CDF and its Research Station, as well as, on Galapagos conservation in general were taken:

- In London the 15th International Zoological Society Congress passed a resolution supporting IUCN’s proposal “to establishing on the islands an international biological station”.

- In Paris UNESCO decided that another Galapagos study needed to be organized after the Eibl- Eibesfeldt /Bowman mission in order to prepare definitive plans for setting up the research station. Jean Dorst, Deputy Director of the Paris Natural History Museum, undertook that mission. He had only six weeks, but accomplished a lot, mainly in working with government officials in Quito. He confirmed with them that the Station should be constructed in Tortuga Bay and received the governmental concession of 4 to 5 hectares in that location for that purpose. The preliminary agreement, signed by the Ecuadorian Foreign Minister, also lists other forms of support of the Government and Dorst went into much detail on building material and what infrastructure would be needed for transportation: a road to Tortuga Bay, deepening of the entrance to the Bay, etc.

- In Quito, at the same time, the Government drafted a decree to create (a) National Park(s). In the beginning, the understanding was that each island would be a separate National Park. In his report, Jean Dorst strongly supported the national park plans laid out in that draft and suggested that a “nature conservation service”, which would have to be created to supervise and control these National Parks, should be placed under the Governor of the Islands. The Galapagos National Park was legally created by presidential decree the following year and it was placed under the Ministry of Agriculture.

The legal creation of CDF seems to have been a fairly unspectacular act: Under the leadership of Julian Huxley, first General Director of UNESCO an Executive Council was formed consisting essentially of a core of those who had pushed the idea in London plus two people representing the Ecuadorian Government. The organization was established in Brussels under Belgian law on July 23rd, 1959, one hundred years after the publication of Darwin’s “Origin of Species”.