The Charles Darwin foundation has just released a new way for people to quickly identify introduced and invasive terrestrial invertebrates. This blog explains in detail how the idea was realized and what it can be used for.

I am an Ecuadorian, and the first time I visited the Galapagos Islands I was 5 years old. I’d come on holiday with my family, we arrived on San Cristobal Island. To this day, I still remember the bright colors of the fish, that could be seen from the pier through the crystal clear water. Not only was this a memorable trip, but for me it was it’s what started my passion for Biology.

I love nature, but what really attracted me is the diversity of shapes and colors of the insects, this is something I always found fascinating. Thanks to the financial support of my parents and several scholarships, I had the privilege of specializing in Taxonomy and Evolution of Diptera (Insects that have two wings, such as the flies).

This then allowed me to travel and to have gained work experiences in continents such as America, Europe and Africa. All these experiences have enriched my personal and professional development. However, my dream was to always to work in the Galapagos.

Near to the end of my post-doctoral stage in France, I was in the search for a new project, I found an announcement from the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF) that was looking for a Principal Curator for the Terrestrial Invertebrate Collection (ICCDRS).

It was the opportunity I had always dreamed of! Personally, I believe that all dreams can be achieved with passion, work and discipline. I decided to apply, although honestly I didn't have much hope for being selected.

After a rigorous process of selection for the job, which included three interviews by video-conferences at 4:00 am Paris time, 12:00 am Puerto Ayora time, I got the position. I organized the move from France and to Galapagos, with a lot of expectations for live in a Natural Park, and to join the team at the CDF Natural History Collections. After a bit more than a year, I can say, it was one of the best decisions of my life. Nowadays I am happy, contributing with my experience and knowledge to the preservation of world natural heritage.

The ICCDRS preserves more than 35,000 specimens which make it the largest repository of Terrestrial Invertebrates from Galapagos in the world (Charles Darwin Foundation, 2019). Since the beginning, the work has been intense, a valuable learning experience and extremely rewarding. I have been able to develop leadership skills and I have also realized my dream of participating in expeditions to remote areas of the Galapagos archipelago.

My team consists of curators, curatorial assistants, volunteers and collaborator’s researchers national and international. We all share the same goal, to contribute our expertise to the conservation of Galapagos, the natural laboratory of the world.

“Invasive Species are possibly the greatest manageable threat to Pacific island economies and their sustainable development” Pacific Invasives Partnership.

One of the greatest threats to Galapagos are the introduced species (Mauchamp, 1997; Peck, Heraty, Landry, & Sinclair, 1998; Schofield, 1989; Toral-Granda et al., 2017), and the terrestrial invertebrates, with more than 560 species is the most prolific non-native group (Causton & Sevilla, 2006). Therefore, it was paramount the need to identify the most common species, their geographical distribution and to know their effects. This is where we had the idea to make a poster, something easy to understand, with updated information from specimens deposited in the ICCDRS and that can be distributed free of charge to the local population.

From the beginning I had the support of Patricia Jaramillo Díaz, Coordinator of the CDF Natural History Collections, who introduced me to her collaborator Anna Traveset, from the Mediterranean Institute of Applied Ecology (IMEDEA-CSIC), from Spain. Thus, we undertook a collaborative work that, in addition to the staff of the CDF, involved the Agency for the Control and Regulation of Biosafety and Quarantine for Galapagos (ABG) and the Directorate of the Galapagos National Park (DPNG).

“Not all non-native species are invasive. To be invasive, a species must adapt to the new area easily. It must reproduce quickly. It must harm property, the economy, or the native plants and animals of the region” Invasive Species, National Geographic.

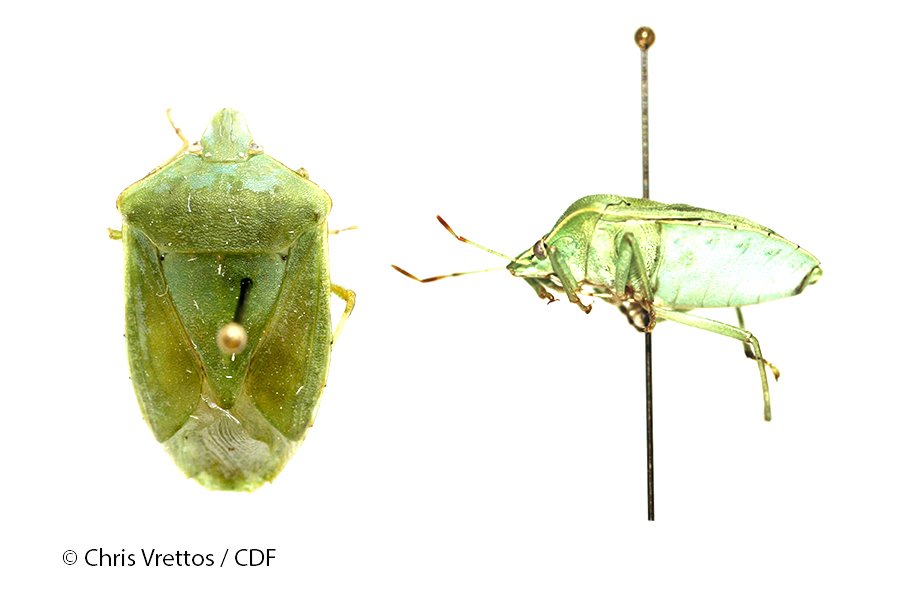

We started by conducting a search for the most common introduced terrestrial invertebrates, particularly invaders and pests deposited at the ICCDRS, and with collaboration of the ABG, we selected 20 representative examples of these species. We then determine the most useful morphological traits for identification and photograph them. To safeguard the integrity of specimens, we settled a protocol and each individual was photographed in dorsal and lateral perspectives.

The photographs taken were used to make illustrations for each species, emphasizing their most useful morphological traits for identification. The design of each species was carried out in collaboration with the IMEDEA Terrestrial Ecology Group.

We also compiled all information related to the geographical distribution of each species, which is available on the dataZone. The specimen records were confirmed and geographic coordinates for each record were plotted on the map. Based on a consensus of specialists from CDF, IMEDEA, DPNG and ABG, we stablished the current status of the species in Galapagos.

Finally, information in Spanish and English was included for all species and two products were developed: an easy-to-go brochure and a wall poster which is free accessible through the CDF quick identification guides.

The species shown on the poster cause serious damage to endemic animals, plants and economic harm to the people from the Galapagos, but also affect other areas in the world, on which they are classified as invasive species. My hope is that these materials will contribute to the control and eradication of introduced species so that, in the future, more children (Like me when I was 5 years old), can enjoy the amazing natural spectacle of Galapagos.

“You are capable of more than you know. Choose a goal that seems right for you and strive to be the best, however hard the path. Aim high. Behave honorably. Prepare to be alone at times, and to endure failure. Persist! The world needs all you can give” E. O. Wilson

Special thanks to: Patricia Jaramillo Díaz, Anna Traveset and Violeta Rafael, for being inspiring women; my family for their enduring support; Helmsley Charitable Trust and Lindbland Expeditions, National Geographic, for their financial contribution to the maintenance of the CDF Natural History Collections.

References:

Causton, C. E., & Sevilla, C. (2006). Latest Records of Introduced Invertebrates in Galapagos and Measures to control them. Galapagos Report, 2007, 142–145.

Fundación Charles Darwin. (2019). Annual Report 2018. Annual Report 2018.

Mauchamp, A. (1997). Threats from alien plant species in the Galápagos Islands. Conservation Biology, 260–263.

Peck, S. B., Heraty, J., Landry, B., & Sinclair, B. J. (1998). Introduced insect fauna of an oceanic archipelago: The Galápagos Islands, Ecuador. American Entomologist, 44(4), 218–237.

Schofield, E. K. (1989). Effects of introduced plants and animals on island vegetation: examples from Galápagos Archipelago. Conservation Biology, 3(3), 227–239.

Toral-Granda, M. V., Causton, C. E., Jäger, H., Trueman, M., Izurieta, J. C., Araujo, E., … Garnett, S. T. (2017). Alien species pathways to the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. PloS One, 12(9), e0184379.