From the Galapagos to Panama (and back): Satellite tracking reveals round trip migration by pregnant scalloped hammerhead shark to coastal birthing grounds

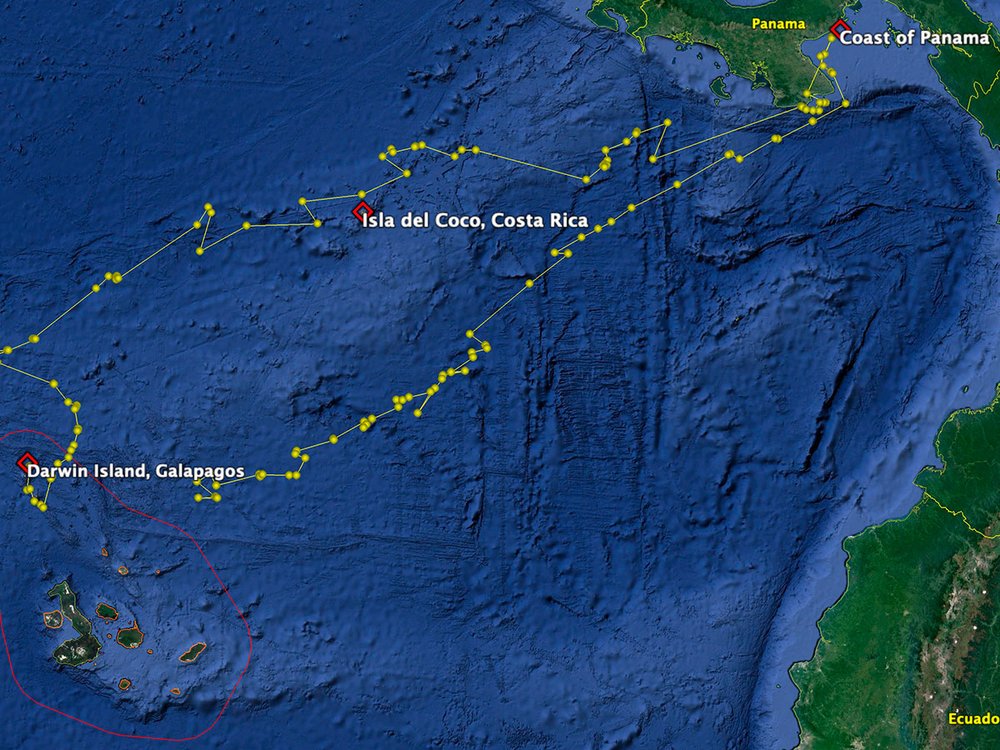

Cassiopeia, the pregnant scalloped hammerhead shark tagged last February with a satellite transmitter at the Galapagos Marine Reserve, has reached the coasts of the Gulf of Panama, a known nursery area for this species. After covering more than 4,000 km, Cassiopeia has provided the first round-trip satellite track between this oceanic archipelago and birthing grounds located on the continental coasts of Panama for this Critically Endangered species.

In a research project made possible by a multi-institutional collaboration between the Charles Darwin Foundation’s shark ecology project, the Galapagos National Park Directorate (GNPD), the Save Our Seas Foundation Shark Research Center Center and Guy Harvey Research Institute at Nova Southeastern University (USA), researchers used satellite transmitters to follow in near real-time the movements of pregnant hammerhead sharks that aggregate at the beginning of each year around the northernmost Galapagos islands of Darwin and Wolf. These very large females display very distended abdomens, a clear sign of a late pregnancy. Scientists also time the tagging of pregnant hammerheads in February, which is just before newborn scalloped hammerhead sharks start to be recorded around the Pacific coast of Panama.

Previous studies by other research groups, including members of the Migramar network have revealed inter-island movements of scalloped hammerhead sharks between the Galapagos, Isla del Coco and Malpelo oceanic islands. This current ongoing research builds on those efforts, by further investigating the movement of pregnant sharks to birthing grounds located on the continental coast of the Pacific coast of the Americas.

“This satellite track provides definitive evidence of the connectivity between the Galapagos Islands and birthing areas on the mainland coast of the Americas for this critically endangered species”, said Dr. Pelayo Salinas de León, Senior Marine Scientist at the Charles Darwin Foundation and Save Our Seas Foundation Conservation Fellow. “Cassiopeia was extremely fortunate to survive this epic migration across kilometers of fishing hooks and nets that have been laid in her migratory route by fishing fleets. Unfortunately, several other sharks we have tagged during the past two years were fished while migrating towards the mainland coast. If we are to save the Tropical Eastern Pacific scalloped hammerhead population from extinction, we need to protect their travel corridors and impose much stricter fishing regulations across the region”, added Salinas-de-León.

The scalloped hammerhead shark was categorized in 2019 as Critically Endangered by the Red List of Threatened Species issued by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), based on estimated global populations decline of >80% over three generation lengths (72.3 years). Despite this critical conservation status, which is at the same threat level as the charismatic Eastern gorilla (Gorilla beringei) or the Javan Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus), fins from scalloped hammerhead sharks fished across the Eastern Pacific continue to flood shark fin markets mainly located in Asia.

“This round trip migration between the Galapagos aggregation and the mainland coast so beautifully demonstrated by Cassiopeia, combined with the high genetic connectivity between these two areas documented by our studies, is allowing a holistic picture of the geographic linkages of hammerheads in this broad region to emerge”, says Prof. Mahmood Shivji, director of the Guy Harvey Research Institute and Save Our Seas Foundation Shark Research Center at Nova Southeastern University. “We hope these findings will help Tropical Eastern Pacific nations implement urgent management measures for protecting pregnant sharks while they are undertaking such important round-trip migrations to the coast, and also reduce fishing pressure in the nurseries, so this vital cycle of life connections can be maintained to preserve this critically endangered and iconic species”.

This ongoing research was possible thanks to the generous support of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Save Our Seas Foundation, Guy Harvey Ocean Foundation, Roller Coaster Road Productions, Mark Rohr and Mark Qi Wong.