On February 15, members of two multi-country working groups attended a workshop hosted by the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF) and the Galapagos National Park Directorate (GNPD) to share updates on research to conserve Darwin’s finches and other Galapagos landbirds and protect them from their number one enemy, the parasitic fly Philornis downsi. Researchers and collaborators working on the Philornis project now span 21 institutions from nine countries, highlighting the international efforts to control this invasive fly. Introduced to the Galapagos Islands about 60 years ago, this fly has become the principal threat to the survival of 20 native and endemic landbird species. The larvae of this fly parasitize and suck the blood of chicks, often causing all nestlings to die.

Birgit Fessl, coordinator of the Galapagos Landbird Conservation Plan, believes that the ongoing bird counts on all islands will allow CDF and GNPD to get an idea of the current status of bird populations. She explained:

“The insectivorous birds (Warbler Finch, Vermilion Flycatcher, Large Tree Finch) and island endemics (Mangrove Finch and Medium Tree Finch) are the most threatened by Philornis downsi at the moment.”

Gustavo Jiménez-Uzcátegui (CDF veterinarian) highlighted that landbirds in Galapagos are not only threatened by this fly, but also by climate change, human interactions, introduced species (especially cats and rats), pathogens and parasites, and contamination.

While researchers work hard to find control methods for Philornis downsi, Francesca Cunninghame (CDF), GNPD and collaborators at San Diego Zoo Global and Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust have been working to protect the most vulnerable bird in the Galapagos, the critically endangered Mangrove Finch, of which there are less than 20 breeding pairs left worldwide. By bringing eggs into captivity and protecting chicks from attack from Philornis downsi, they have managed to increase the number of juvenile mangrove finches by over 50%.

Last year they also tested a ‘short-stop method’ to control Philornis downsi in nests which has been developed by scientists at the University of Vienna. This method involves injecting a low toxicity insecticide into the base of the nests where larvae hang out when they are not feeding on chicks. This method has been successful in reducing parasite density in the nests of several finch species. However, “insecticides aren’t viable in the long run and can only be used in small areas and reachable nests. We need to find a long-term solution,” stated researcher Sabine Tebbich from the University of Vienna.

It is a race against time to find a long-term control method that will ensure the recovery of Galapagos landbird populations. “The big nut to crack is to find a way to breed the fly in the lab so that we have a continuous supply of flies for our studies. Once this has been accomplished, we will be able make significant and fast progress in finding a viable long-term control method,” claimed Charlotte Causton, Coordinator of the Philornis Strategic Research Plan.

The complexity of this research is mind-boggling. Although CDF researchers and collaborators are making huge strides in understanding the fly’s entire lifecycle, many mysteries still remain, the biggest being why flies won’t breed in the lab even though they are found in all kinds of habitats. Factors such as temperature, humidity, sunlight, and diet must all be taken into account.

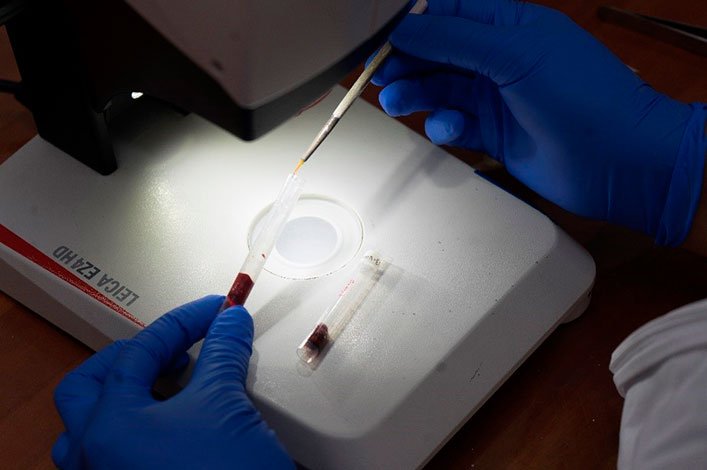

Boaz Yuval and colleagues at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem are working on describing the bacterial community of the gut of Philornis downsi flies because it is possible that larvae reared in the laboratory are missing bacteria that are crucial to development. Meanwhile, Stephen Teale and Alejandro Mieles at SUNY-ESF are investigating the role that pheromones play in mating. By understanding the compounds in pheromones, it might be possible to improve mating success in the lab as well as use these attractants in traps to target Philornis in highly invaded areas such as the mangrove forests of the Mangrove Finch on Isabela Island.

One possible long-term solution for controlling Philornis downsi is biological control, involving the importation of a natural enemy that selectively targets the fly. Luckily, George Heimpel (University of Minnesota) and colleagues seem to be on the right track, as both fieldwork and lab tests suggest that a parasitic wasp named Conura annulifera only parasitizes Philornis flies. If studies continue to show this, the next step will be to request approval to introduce the wasp to the quarantine facility at the Charles Darwin Research Station to conduct tests to ensure it won’t negatively affect Galapagos insects.

The Galapagos National Park Directorate (GNPD) plays a fundamental role in this bi-institutional project. As many researchers stated, without the management of invasive species like blackberry, bird habitat destruction would be much worse. Christian Sevilla elaborated on the GNPD’s role:

“The Galapagos National Park supports administrative matters and the implementation of possible control methods to combat Philornis in vulnerable areas.”

Workshops like the one held at the Charles Darwin Research Station are highly informative and great places for researchers from all over the world to discuss ways to conserve Galapagos biodiversity. Enzo Reyes, a PhD student at Massey University, highlighted the importance of speaking to other collaborators at workshops and of getting greater funding for studying the Philornis fly and landbirds in general. Participants have signed a declaration with a large group of partners to highlight the importance of this research.

This is one of the Charles Darwin Foundation’s many projects in Galapagos and we depend entirely on the generosity of our supporters. If you would like to help us find a solution to the invasive fly and save Galapagos landbirds, please donate now.