Past and Present of Fisheries in Galapagos

Fisheries is one of the oldest economic activities on the Islands, which were annexed to Ecuador in 1832. One of the first attempts of colonizing the islands, which do not have ancestral cultures, was in the early 1920s by a group of Norwegians settlers that intended to whale, and fish and can groupers, lobsters and sea turtles. This attempt ended in the late 1920s when their boiler exploded. However, because of these attempts and in order to protect the unique marine communities of the islands, the Galapagos Marine Reserve (GMR) was created in 1998 as a multi-use protected area.

The declaration of the GMR also came with a ban on industrial/commercial fishing but allowed artisanal ones in specific areas under a coastal zoning scheme. Despite the creation of the GMR the number of fishers rose to over 1200, particularly during the sea cucumber boom in early 2000s, until its collapse in the later part of that decade.

At present, although there are over 1200 licenses, fishing is only carried out by ~400 fishers and is the least managed of economic activities. Of the more than 60 fish and invertebrates fished only 4 have species-specific regulations. Fin-fishes are, along with lobsters, the largest fishery and mostly targets bottom dwelling fish such as groupers and snappers that are commonly slow growing animals that reproduce later in life and are therefore very vulnerable to unregulated fishing.

The problem: lack of information.

How do we intend to fix it?: by studying young fish and invertebrates in their environments

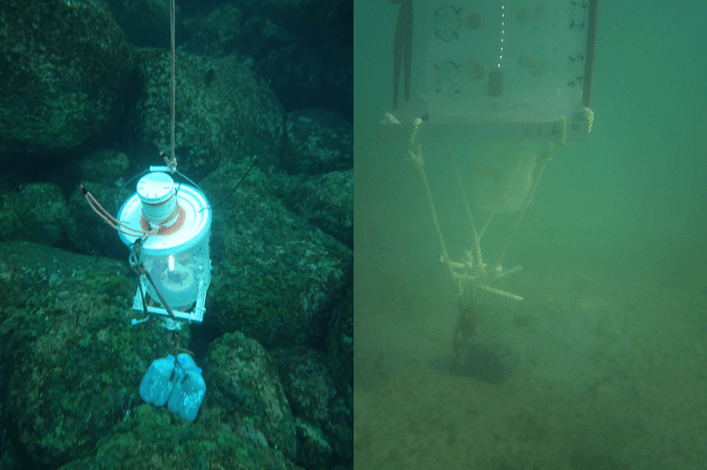

One of the main problems for the Galapagos National Park Directorate (GNPD), which manages the marine resources in the GMR, is the lack of information on these animals, particularly during their initial lives. To fill these knowledge gaps, scientists at the Charles Darwin Foundation’s Marine Science Program are studying biological communities present in mangroves, sandy beach surf zones and other coastal environments, which often function as home for young fish and invertebrates. We use a combination of field, lab and computer analysis to carry out these studies. In the field we use traps that employ light to attract animals, baited video cameras and a traditional fishing hook-and-line method called empate.

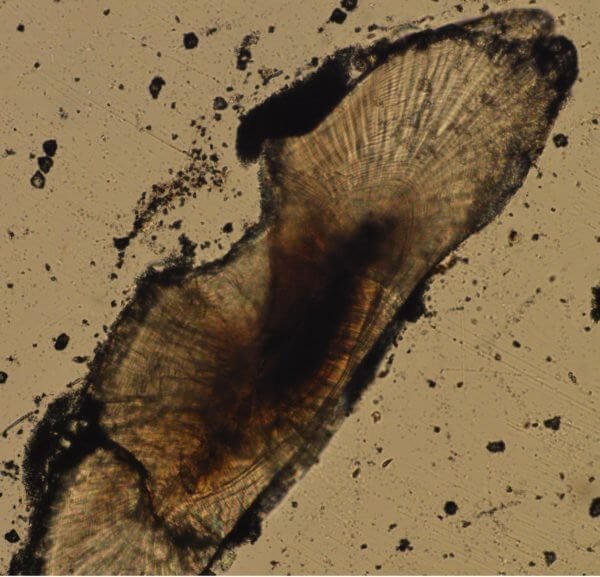

In the lab, besides describing the animals collected, we analyze fish otoliths or ear bones. These bones are analogous to trees in that they have daily and annual rings that allow us to age the animals and estimate their growth since the width of the ring is related to how much the fish grew during that particular time.

We hope the information from our studies will allow the GNPD to take management actions, such as setting size and catch limits, or closure to the fishery during reproductive periods, to reduce the impact of fishing on these iconic animals.

This blog was written as an exercise of a National Geographic Storytelling bootcamp carried out at the Charles Darwin Research Station in Puerto Ayora, Galapagos, Ecuador.