Written by: Jack Lo Lau / Mongabay Latam

This article was originally published in Mongabay Latam.

How is a small fruit fly able to affect the finch population?

What do the dwarf penguin, the flightless cormorant and the elegant albatross have in common?

The life in Galapagos surprises you every second. A visit in this Archipelago is like entering a natural laboratory where you learn about the evolution of species by observing and feeling. You find sea lions, turtles, birds, penguins, and even friendly sharks that appear right in front of you without making you feel threatened. Not surprisingly, the rules in the Galapagos Marine Reserve are very strict and violations are sanctioned with penalties of thousands of dollars for those who cause damage in any way to any species or try to take something, even a little sand as a souvenir. This warning is given to the more than 200 000 tourists that arrived each year to this inhospitable corner of the planet. The first island was formed five millions years ago, and scientists and investigators continue to be impresses how life in Galapagos keeps moving forward. The species continue evolving, changing forms and sizes, and some islands, such as Isabela or Fernandina, are still in the process of formation. An example is the volcanic eruption registered in 2009. To show how impressive the Galapagos Marine Reserve is, there is a group of people in pursuit of its best conservation by producing more information and research supported by the Charles Darwin Foundation, a Belgian institution founded in 1959 that works together with the Galapagos National Park Service (GNPS) to promote scientific investigation in the Archipelago. It is said that to know the Park, you need to know the species living in it. This time, we are going to focus on its peculiarities and endemic land and marine birds (that live and spend most of their time in the Pacific Ocean).

A natural paradise

Galapagos covers an area of 133 000 square kilometers (km) and is located 1000 km away from the Ecuadorian coast. It has 13 large islands with a surface area greater than ten square km, six medium islands between one and ten square km, and 215 small islets. There are daily flights from Guayaquil or Quito to get there. It is the second biggest marine reserve in the world, after the Australian Great Barrier Reef, that receives visitors from all over the world to dive in its famous waters. The reserve was created in 1998 and this year it celebrates its nineteenth anniversary. In recent decades, a lot of investigation has been done, first by the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF), then by other distinct organizations that have seen the conservation if this unique place as a priority. Its importance was recognized in 1978 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), when Galapagos was nominated as a Natural Heritage Site for Humanity. In addition, in recent years it has been recognized by different international conservation organizations as Ramsar Site, Whale Sanctuary and Biosphere Reserve. More than 2200 species have been identified living in the reserve, 25% of which are endemic, that is to say, can only be found in Galapagos. Thus, it is not a surprise that 97.5% of the surface area in the Archipelago is protected. Only 2.5% can be visited by tourists and the local population. And even that small portion is very impressive.

Land: Darwin finch in danger

From the moment you step onto Galapagos a special energy is felt. Trees and cactus you never saw before. Birds posing in your chair to receive you with a beautiful whistle. Sea lions and rays jumping a few meters from the shore. As you experience it, your days at the reserve become more spectacular. Just imagine Charles Darwin, back in 1835, carefully observing these animals, seeing their similarities and differences. The most emlematic bird of Galapagos arrived a million and a half years ago, and it is the finch. For many, the symbol of evolution too. It measures between ten and twenty centimeters and weighs around twenty grams, similar to a box of cigarettes. It is a small bird with brown and black colors, not very flashy when compared to the giant tortoise or the hammer head shark. According to Leif Anderson, of Upsala University in Sweden, in a study published by Nature magazine, Darwin was impressed by the diversity of the beaks of this specie. In the archipelago, you can find seventeen different species of finches and all of them differ mainly by their beak. Each one evolved depending on the food that was most available to it and the environment in which it lived. The same finches are not found on all the islands. They are distinguished by what they eat, which can be seeds, fruits or insects. Those with large, thick beaks can split seeds and have a song which is simpler and easier to reproduce. Those who have the smallest and most delicate beaks are adapted to eat insects. In 1973, Peter and Rosemary Grant, professors at Princeton in the United States, analyzed nearly 20,000 specimens of finches from twenty-five generation, and showed that they were changing their beaks and sizes in response to environmental changes.

"Each island has its range of species. Some are distributed in many places, such as the small ground finch (Geospiza fuliginosa), or the Galápagos flycatcher (Myiarchus magnirostris). Others are only found on one island, such as the medium tree finch (Camarhynchus pauper) in Floreana. The species adapt to their environment. Everything will depend on the source of food, other species already present, and the competition between them. The beaks are used as tools to facilitate the exploitation of one type of food. And this specialization of each of the species reduces competition with others. With the isolation of sites, it is very likely that in a few thousand years we will have several new species for science to investigate," Birgit Fessl, an Austrian researcher in charge of the Charles Darwin Foundation's ground bird conservation project, told Mongabay Latam. She also makes a distinction that "land birds are referred to in this way because they feed on seeds and animals found on land. As opposed to the seabirds that spend most of their time on the sea and feed on what they find there," said Fessl, who has been working with Galapagos land birds since the nineties.

In recent decades, these birds have had many threats that the Reserve has had to control, such as the plague of rats or the presence of cats that are its main predators, which we will see later. However, in 1997 the strongest threat they have ever faced was reported: a fly (Philornis downsi) that weakens the eggs and the chicks of the birds. "It was by chance. We were studying the carpenter finch (Camarhynchus pallidus), we wanted to know if its way of using other tools like leaves or branches to build or defend itself, was something learned or acquired. We took two chicks out of their nests, took them to the laboratory, and the next day one of them died. We found larvae as large as two centimeters, all filled with a black substance. I had never heard of these in Galapagos," remembers Birgit Fessl, who says that at present they have identified fifty species of this fly that are parasitizing birds. How do they attack? "The fly lefts its eggs in the nest and the larvae of the flies develop with the blood of the chicks. They get inside the body of the birds, until they kill them. There is a very high rate of mortality," says Fessl.

According to Dr. Charlotte Causton of the Darwin Foundation, "it is one of the most invasive species in the Galapagos" and the most serious threat to many land birds. "We are conducting research and we still do not have a baseline to determine how much this fly has affected the Galapagos birds. However, in some species we can determine some things. As in the medium tree finch (Camarhynchus pauper), whose reproductive success is practically nil. At most it approaches 10%. It is very worrying," says Fessl, who, along with a team of professionals and international organizations, is working on different strategies to eradicate this problem.

In 2012, an international Philornis team was formed, bringing together twenty institutions from eight countries: Ecuador, the United States, Australia, Austria, Argentina, Israel, Panama and Trinidad and Tobago. It is led by the Charles Darwin Foundation and supported mainly by the Galapagos National Park Directorate, BirdLife Austria biologists, the Galapagos Ministry of Agriculture (MAGAP), the Mediterranean Institute of Advanced Studies of Spain (IMEDEA) and dozens of scientists and researchers from Ecuador and abroad who come to contribute their knowledge and experience. They have been studying the nests and collecting flies to develop less risky methods for the suppression of this pest in the islands. "We are working in different ways. First, by placing pesticides in the lower parts of the nest, where the larvae are located, to eliminate them. Or by introducing pesticides to sterilize them. This is very laborious because it has to be done nest by nest. The other technique we are developing is to create a scent that attracts flies. However, it is quite complicated because for example last year it was very dry and there were no flies to do the tests. We are also analyzing how to sterilize the males so that when they have relations with the females, the result is sterile eggs and an end to the pest," says Birgit Fessl, who is optimistic about the work done and the future to come.

In environments as fragile as in Galapagos, a even minimal change can be felt and becomes evident. "For example, this plague must have come as adult flies, on damaged fruit, several decades ago. Now, I think that would not happen because they have improved the controls and there is a good protocol for the entry of products to Galapagos," says Fessl, who continues to be amazed by the fragility of this reserve. "The extreme conditions in Galapagos attract scientists from around the world, who are captivated by the changes that are easily observed. The living conditions of animals and plants change very quickly. In a few generations of birds and plants you can see how they adapt," said the Austrian conservationist who hopes to finish with a first baseline population of finches in a couple of years. For the time being, the Charles Darwin Foundation and the Galapagos National Park Directorate have taken steps to raise finches in captivity and protect juveniles from this plague, which has been unstoppable so far. It is worth noting that the mangrove finch (Camarhynchus heliobates) is experiencing the most critical possible situation. Only eighty individuals remain in the wild.

The flight of the marines

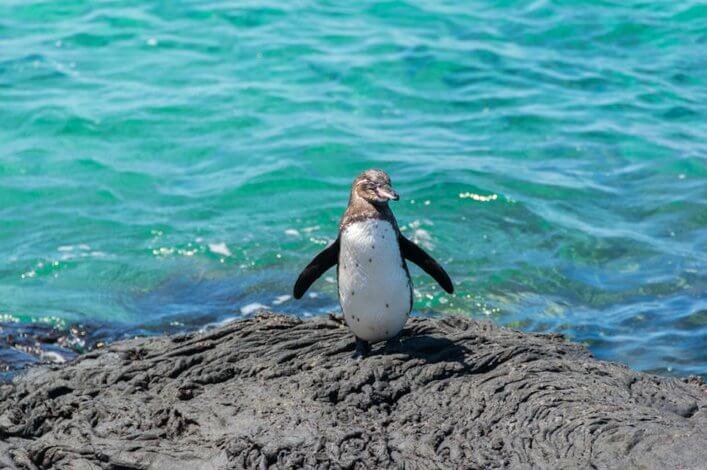

The Galapagos penguin (Spheniscus mendiculus), the flightless cormorant (Phalacrocorax harrisi) and the waved albatross (Phoebastria irrorata) are seabirds that can only be found in this corner of the planet. And even here you do not cross their paths easily. Each has its own motives. It is easier to encounter turtles, finches, sea lions or iguanas, swimming around or sunbathing on some of the sublime beaches, than it is to find these seabirds. This is how their presence makes the thousands of tourists who want to take home the difficult figurine delirious.

For seven years, a group of professionals from Ecuador and the rest of the world has been working on a seabird project that monitors the three main birds of the islands for the sole purpose of achieving long-term conservation, identifying their threats and working to control or eliminate them. Get ready to learn more about the unique tropical penguin, the spectacular cormorant that lost its ability to fly and the albatross, one of the largest and fastest birds in the world.

“We chose these three species because we consider them key. If you analyze and have information on these representative species, you can know what is happening with the ecosystem, with the habitat, with the islands. In addition, they are on the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) red list and we need to maintain our stewardship for them. For example, with the penguin and cormorant, we can understand what is happening inside the Galapagos and with the albatross we look to see what is happening further afield, since they reach as far as Colombia, Peru and Chile," said Gustavo Jiménez, Senior researcher, penguin, cormorant and albatross specialist from the Charles Darwin Foundation, to Mongabay Latam. Sr Jiménez started this project with albatrosses in 2009, and added penguins and cormorants the following year.

The Galapagos penguin (Spheniscus mendiculus) is endemic to this archipelago and its population is the northernmost in the whole world. They weigh no more than two and a half kilos, and are no more than fifty-two centimeters in height, making them about as tall as a stair-step. Only a trained eye can distinguish them in the distance. Its black head and white belly with small black spots are easily confused with the volcanic rocks that are usually around the islands. Many of these peculiar birds are found in the islands Fernandina and Isabela, located in the westernmost part of the archipelago.

"It is the third smallest penguin species in the world. It is also the only one that lives in the tropical zone and breeds in the northern hemisphere. Its population at the moment is stable but is fluctuating due to climate change. When the El Niño phenomenon occurs, which is occuring with increasing frequency and intensity, we find less food available, penguins have to move farther away to feed themselves, and this exposes thems much more to their predators (sharks). They also suffer from other threats, such as competition with other species and even the presence of humans," said Jiménez, who investigates these penguins on Isabela Island and the little-visited Marielas islets, home to the largest populations of this species: between 50 and 100 individuals.

As Jiménez says, the El Niño Phenomenon is its main threat. In 1982, the population was reduced from 1500 to 300. In 1998, the change was from 1200 to 400. And in 2015, it was less diminished, reaching about 800." The problem when this happens is that there is no reproduction," added Jiménez. This species spends most of the time eating, swimming, caring for their young or being with other penguins. They only leave during the day and at night they rest. They are used to being near the coast, swimming long distances, up to 50 kilometers a day, and diving deep. Experts say they have found them diving to 50 meters deep. They usually feed on small fish such as anchovy (Cetengraulis mysticetus) or sardines (Sardinops sagax). However, the stress caused by lack of food when El Niño or La Niña occurs, and the different threats that do not allow them to live in peace, represses reproduction and further depletes their already small population.

"At present there is a population in Galápagos approaching 2000 penguins. And we have been conducting ecological monitoring that analyzes survival, mortality, reproduction, their diseases, their life in relation to climate change and also the impact of human activities such as fishing and tourism," said Jiménez, who has been working with the penguins, along with the Galapagos National Park Directorate, San Francisco University of Quito, Colorado State University and the University of Missouri. In the coming months there will be more news on the status of seabirds and their conservation status.

The flightless cormorant or Galapagos cormorant (Phalacrocorax harrisi) for many, is one of the rarest birds that exist. Apparently, having almost no predators led them to stop using their wings, and they are the only member of their species that can not take flight. Almost everything is done on land and swimming in the water. They do not venture far from shore and searches for food on the seabed, reaching up to 70 meters deep. Their strong legs help them to move quickly in the water. They feed on octopus and small fish. They do not reach more than 100 centimeters in height and do not exceed five kilos in weight. hey are black and gray. They do not have bright colors in their plumage, perhaps to go unnoticed, but their strong beak enables them to fight and hunt they favorite prey, octopuses, and their turquoise eyes are found to be enchanting by many. Their plumage is not waterproof, so it takes longer to dry each time they dive for food.

As with the penguins, they suffer from climate change. After 1982, from being 800 individuals, they became 400. "The population of cormorants has fallen with El Niño, but not as drastically as with penguins. In the last ten years their population has grown but they are scattered. In Fernandina and Isabela we can find them in large colonies. But when I say big, we are talking about 30 to 20 individuals. However, in recent years record numbers have been registered, such as more than 2,400. With these data, we could say that they have stabilized and are now increasing, " Gustavo Jimenez said optimistically to Mongabay Latam, who also said that they are working to produce more information to eliminate or control their main threats: rats and cats, "introduced species that must have been transported by ship since human arrival on the islands," which are the main headache of scientists, technicians and conservationists of the park. Although they are also the occasional prey of snakes, owls, sparrow hawks and sharks.

Studies of these species are carried out in two different places, to analyze their behavior in different situations. "They can be found on Fernandina, which is a pristine island, and also on Isabela, which is an island where there are introduced species such as cats. We are analyzing their behavior and we see how they are developing in these two places with different threats," said Jiménez, who also highlights the support for this work by all the institutions involved such as the Galapagos Conservancy Trust, Lindbland National Geographic, Penguin Fund Japan, Blue Planet Film, San Francisco University of Quito, Colorado State University and University of Missouri.

We now turn to the Galapagos albatross (Phoebastria irrorata), waved albatross or wavy albatross. This imposing bird nests exclusively on Española Island in the Galapagos archipelago. It arrives at the end of March and stays until the end of the year. It usually builds its nests in lava areas and when it is not in the islands, it can be found in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru or Chile. It loves squid, the base of its diet, along with small fish. The size and speed of this bird is very impressive. When it extends its wings it is as long as a car. It can live up to 40 years and reach speeds up to 90 kilometers per hour. It is in critical danger of extinction, as well as penguins and cormorants, so there is a clear intention of the Galapagos National Park and different Ecuadorian and foreign institutions to produce more information about this species and protect it in the best way possible.

"Now we are studying it on two points of Española Island, Punta Suarez and Punta Cevallos. We estimate that its population is around 30 000 individuals. We want to see if its life time has been affected in recent years. We are trying to work with several colonies to see if these samples give us a clear idea of the comprehensive status of this species. Climate change affects albatrosses, just as with penguins and cormorants, but their main threat occurs in the open sea fishery, as many birds die as an unintentional consequence of human fishing activities," said Gustavo Jiménez, who also mentions the importance of the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP), which since 2004 has sought to preserve albatrosses and petrels through the coordination of international activities aimed at reducing the threats of these seabird populations. It protects 31 species of albatross, petrels and shearwaters. Thirteen countries are members: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, France, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, South Africa, Spain, United Kingdom and Uruguay. And as with the waved albatross, other species of albatross in all parts of the world also have unsustainable fishing practices as their main threat. "This agreement is important, because it helps us generate more information around the planet. We are always sharing the data we have and we are in constant communication. This will allow us to implement effective conservation measures for seabirds, on land and at sea," Jiménez said. However, another threat is introduced species, such as mosquitoes that bother albatrosses so much that they are forced to abandon their nests. The situation has begun to be studied more in depth in order to promote measures that confront this apparently harmless insect as well as the possible pathogens that can affect these species.

Facing threats

The main threat to these species is the climate change that is reflected in the El Niño Phenomenon, which is increasingly occuring with greater regularity and intensity. There is not much that can be done to solve this problem, which is why the efforts of the Charles Darwin Foundation, various organizations and the Galapagos National Park Service (SPNG) are aimed at reducing other threats. It is important to control or exterminate introduced species such as cats and rats so they do not continue to attack birds, and to maintain control of the workings of fisheries and vessels, to avoid incidental by-catch and other diseases. "All our efforts and research are done with the intention of reducing the impact of different threats on species. The idea is to be able to control pests, introduced species such as cats and rats, and the work of the fishing operations that transit in the outskirts of the marine reserve, more precisely off the coasts of Ecuador and Peru," said Gustavo Jiménez, who also pointed out that "working to reduce these threats is key, since we are giving these species an opportunity to be stronger and prepared when El Niño arrives, when food is scarce and their populations are always diminished as a result."

And so it goes, 1000 kilometers of the coast of Ecuador. With people generating information, with constantly evolving species and thousands of people arriving here to experience surprises and to marvel at this place that most resembles a fantasy island come true.