Tortoises are not the only ones returning to Española Island (Galapagos Verde 2050)

Author: Luka Negoita

On June 15, 2020, Paúl Mayorga and I set out to deliver fencing supplies and survey 240 endangered Opuntia tree cacti that had been planted on Española Island over the last few years by the Galapagos Verde 2050 project (GV2050). We hadn’t been able to return to this island for ten months due to the Covid-19 lockdown here in the Galapagos. But now, thanks to Washington Tapia of the Giant Tortoise Restoration Initiative (GTRI of the Galapagos Conservancy), we were able to make our first trip back to the island by joining Galapagos Conservancy and the Galapagos National Park Directorate (GNPD) on their trip to return giant tortoises from breeding captivity back to their home island. These tortoises were some of the first ones taken off the island and now are some of the last ones to return.

The recent news has been filled with the incredible story of Diego the tortoise who alone was able to sire almost 1,000 offspring. Together with 14 other giant tortoises that were initially taken from the island, these individuals have helped bring back Española’s population of giant tortoises from the brink of extinction in the 1960s to well over 2,000 as I am writing this blog. Though an inspiring story, the long-term survival of Diego and his kin, just like with any threatened species, will rely on ensuring a suitable habitat where they can thrive once again.

The Charles Darwin Foundation has been collaborating with GTRI over the last 5 years to study how to restore the endangered population of Opuntia tree cacti on Española Island — the giant tortoises’ primary food source (Gibbs et al. 2008).

The current population of Opuntia megasperma var. orientalis on Española is estimated at less than 3,000 individual trees across the entire 23 square miles of the island. Historic expeditions to this island such as the California Academy of Sciences (CAS) Galapagos expedition of 1905-1906 had suggested a historically greater number of Opuntias and even documented this abundance with photographs of the island where the skyline was dotted with forests of Opuntia trees (see photos below). Several factors have contributed to the current declines, including the absence of tortoises and the presence of the introduced feral goats of Española, which were only finally eradicated in 1978 (Gibbs et al. 2008; Márquez et al. 2019; Jaramillo et al. 2018).

Beginning in 2000, several studies conducted by the Charles Darwin Research Station (CDRS) began experimenting with how to bring back the endangered Opuntia species on this island to a healthy population in order to protect the endangered species and provide an adequate supply of natural food for the now growing population of giant tortoises (Atkinson 2007; Coronel 2002). In 2017, the GV2050 project of the CDF, which was started in 2014 to help restore degraded ecosystems of the Galapagos, began implementing a new and large-scale adaptive management program for finally restoring these Opuntias. The essence of an adaptive management program is to begin active restoration while also conducting experiments so that over time we can adapt our restoration efforts and actions towards what works best.

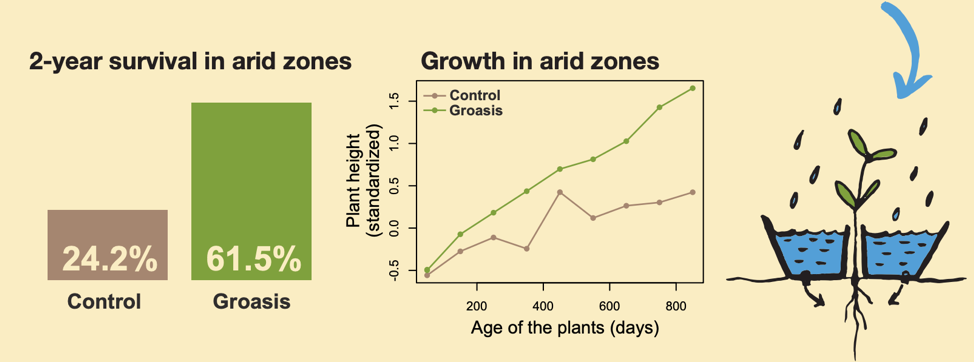

Together with collaboration from the Galapagos Conservancy and Galapagos National Park Directorate, GV2050 began planting Opuntias using experimental designs that begin this restoration process while also testing methods of increasing restoration efficiency. For example, Española has a relatively arid climate which may contribute to a higher mortality in young Opuntias, so we need to find ways of ensuring their survival. Through our recent study on Opuntia restoration on other islands in the Galapagos (Tapia et al. 2019), we found that certain technologies (water-saving technologies) can be used at the time of planting to increase the survival of young Opuntias in arid conditions. We are now testing these technologies, such as the Groasis Waterboxx®, on this island, and so far, the results are promising. We also quickly learned that though tortoises are beneficial to the long-term survival and reproduction of Opuntias by dispersing their seeds (Gibbs et al. 2008), they also love eating the young plants. So, we now use rocks and metal fences to protect these plants while they are young and increase how quickly we can restore this habitat.

To learn from these experiments and continue improving this restoration efforts, we must continue returning to the island to collect data on these plantings—which brings me back to the start of this post: Paúl and I from GV2050 just returned from an amazing field expedition to Española Island to check on our plants, deliver fencing supplies, and continue collecting data.

We spent 45 minutes hiking up the difficult but gorgeous terrain to the “Las Tunas” planting site, where we previously have had to carry over 2400 gallons of water for planting the Opuntias. This time we were able to bring lighter backpacks and check on the two rainwater cisterns that we installed in August of 2019 thanks to helicopter support through our generous collaboration with the GTRI. We deposited the metal fencing that we had brought to the island and then proceeded to visit each of our 240 Opuntia seedlings to record data on their survival.

Though only one day, our trip began at 1 in the morning on Sunday and we were back in Puerto Ayora on Santa Cruz Island at 8 pm. We were physically exhausted but pumped with excitement after finally being able to get out into the field once again. In the same way that Diego and his kin were finally able to return to their home, so too will we once again return hundreds of baby Opuntias that are currently growing in greenhouses cared for by the GNPD and the GV2050 team. It is an honor to continue this monitoring and restoration work on Española Island, helping to ensure the conservation of such an amazing and unique ecosystem.

Learn more about Galapagos Verde 2050 and what we are doing in the Galapagos by visiting our website at www.GalapagosVerde2050.com.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank the organizations and people without which our work in these islands would be impossible: Washington Tapia of the GTRI and our scientific advisor and collaborator James Gibbs, and the Galapagos Conservancy and Galapagos National Park Directorate for their immense support and collaboration through this project. Special thanks to María José Barragán (CDF Executive Director (i) and Science Director) and Patricia Jaramillo Díaz for their comments on previous versions of this blog, revisions and translate to Spanish. Finally, we thank the primary donors that have financed our work thus far: The COmON Foundation and Green Fund of Japan.

References:

Atkinson, R. (2007). Rescuing and restoring the endangered native plants of Española island, Galapagos: Charles Darwin Foundation.

Coronel, V. (2002). Distribución y Re-establecimiento de Opuntia megasperma var. orientalis Howell. CACTACEAE) en Punta Cevallos, Isla Española–Galápagos. Universidad del Azuay, 78 pp.

Gibbs, J. P., Márquez, C., & Sterling, E. J. (2008). The role of endangered species reintroduction in ecosystem restoration: tortoise–cactus interactions on Española Island, Galápagos. Restoration Ecology, 16(1), 88-93.

Jaramillo, P., Tapia, W., & Tye, A. (2018). Opuntia megasperma var. orientalis Howell. In F. C. D. F. y. WWF-Ecuador (Ed.), Atlas de Galápagos, Ecuador (pp. 58-59). Quito: Fundación Charles Darwin (FCD) y WWF-Ecuador.

Márquez, C., Vargas, H., Snell, H., Mauchamp, A., Gibbs, J., Tapia, W. (2019). Why are there so few Opuntia on Española island, Galapagos? (Vol. 2.0, pp. 21-29). Puerto Ayora.

Tapia, P., Negoita, L., Gibbs, J., & Jaramillo, P. (2019). Effectiveness of water-saving technologies during early stages of restoration of endemic Opuntia cacti in the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador. PeerJ Life & Environment, 1-19. doi: https://peerj.com/articles/8156/