Expedition to the bottom of the sea

This is my third week of a month at sea onboard the R/V Falkor (too) together with a group of scientists led by Dr. Roxanne Beinart, University of Rhode Island. I am on board the first of three deep-sea Expeditions planned in the Galapagos from August to November 2023.

The current first cruise is dedicated to exploring the deep hydrothermal vent communities to the NW of the Galapagos at sites within the Galapagos Marine Reserve and in Ecuadorian territorial waters. Collaboration with a great group of scientists and the ocean conservation non-profit Schmidt Ocean Institute has presented a spectacular opportunity to further research for Galapagos and Eastern Pacific marine conservation.

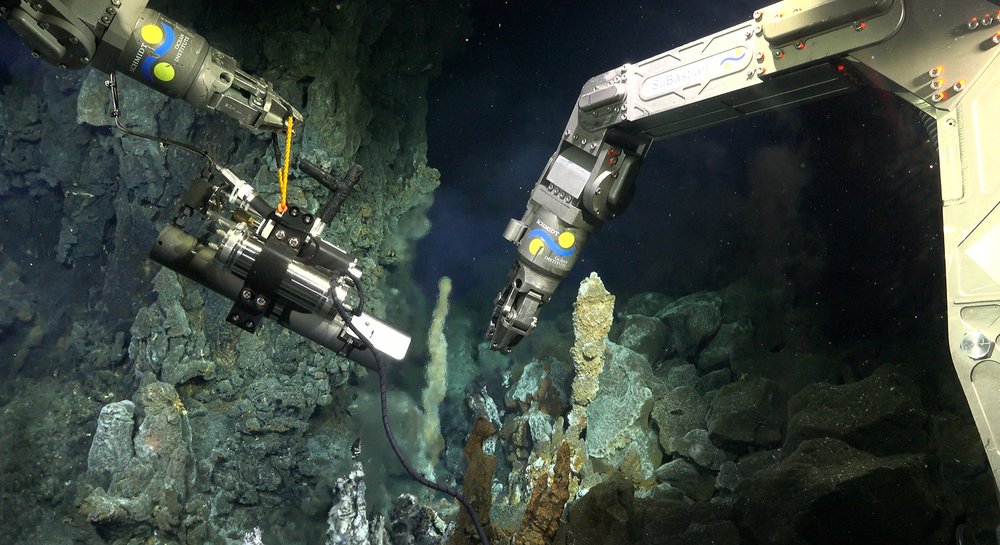

As a high-tech oceanographic vessel operating the charismatic remote operated submersible (ROV) SuBastian - themed as with the ship name Falkor, after the 1979 fantasy novel by Michael Ende, “The Neverending Story” - the technical operation runs almost continuously alongside amazing high quality live-stream broadcasting from the ROV deep on the ocean floor and ship-to-shore experiences to anyone and everybody able to connect on-line.

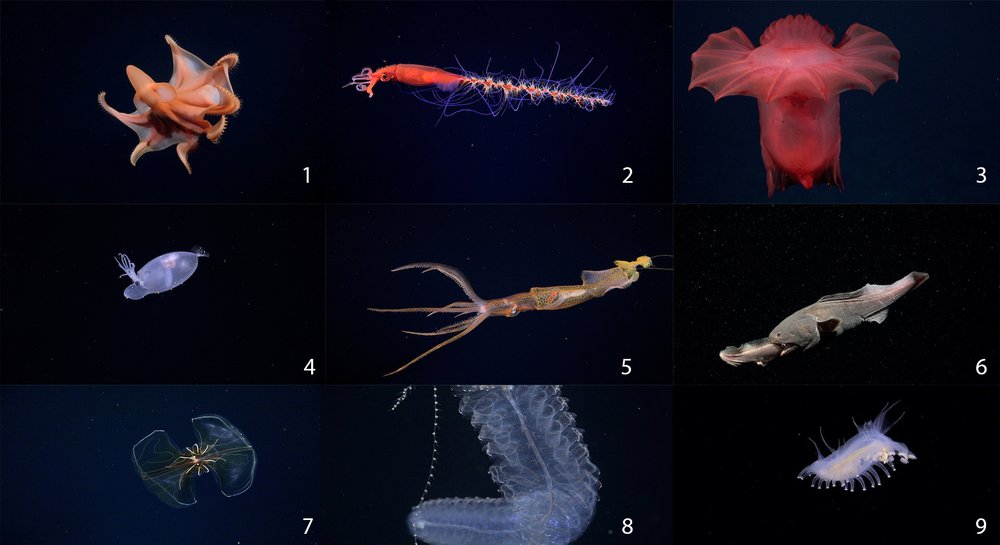

Exploration, is what has drawn us to this remote spot over the Galapagos Spreading Centre. A geologically fascinating, volcanically active fault-line between grinding tectonic plates harbouring some of the strangest, most dynamic marine ecosystems and bizarre yet beautifully adapted creatures known to science. The type of spot where ocean life may have originated, a place where we may find clues to how life could begin on other worlds. What Darwin would have made of it, we will never know, and yet over 160 years later it provides one of the most fascinating case studies for linked geochemistry, biology, and evolutionary science.

The control room

6 am. Coffee in hand, I make my way from my cabin, over a slowly rolling deck (avoiding the occasional meteoric bird splat from Frigate birds and red footed boobies perched high on the cranes), through a small maze of corridors and carefully designed wet labs, arrays of sample fridges and computing control stations, finally arriving at the mission control room.

The mission control room is the beating heart of the expedition. Poised over a barrage of data streams, screens and flashing buttons, there are a handful of hushed scientists, technicians, students and crew who are working around the clock, part of a wider team to explore, characterize and understand a unique hidden submarine world, an incredible 2500m below.

People change shifts to grab breakfast, some head off to rest while for others another day begins. On the screens: an ornate basket-star straddles a bamboo coral, while a ghost white squat lobster pirouettes into view and jetting along in spurts, disappears behind a patch of giant tube worms. All dutifully logged by a bank of observing students poised over laptops.

As the otherworldly scene unfolds kilometres below us, you idly wonder if seeing this could ever become routine. The “on-air” light blinks in the background and you’re reminded this is streamed live to the world.

Exploration for better ocean conservation

In terms of significance for research for conservation of the Galapagos, the R/V Falkor (too), joins the esteemed ranks of exploration expeditions dating back several centuries, such as those led by Taylor in the 1930s, the Californian Academy of Science in 1905, Smithsonian, or William Beebe’s 1925 Arcturus expedition – although admittedly in greater comfort and likely less risk of scurvy.

It joins others that are dramatically helping fast-track deep-ocean science for conservation. This at a time when it is painfully apparent that our future welfare as a species depends upon the decisions we take now to ensure healthy and sustainable global oceans.

Our largely uncharted deep ocean represents more than 90% surface area and includes some of the most emblematic regions such as Galapagos, harbouring irreplaceable biodiversity in the Eastern Tropical Pacific.

CDF’s commitment, alongside that of the Galapagos National Park and a host of partners, is to build findings from the R/V Falkor and similar expeditions into the DNA of adaptive management for the region’s deep-water habitats.

Bridging academia, technology, unprecedented access and outreach, the current R/V Falkor (too) cruise shows the great potential of the private sector to encourage best practices, strengthen relevant knowledge and drive conservation action.

Through collaboration and the dedicated research efforts of groups such as Dr. Beinart and her diverse team of mappers, ocean engineers, chemists, oceanographers, and biologists we are better prepared to support conservation and management through informed technical criteria.

This trip alone will hopefully build awareness for conservation of deep, connected, and fragile hydrothermal vent habitats. Underscoring another chapter in the rich natural heritage of the Islands as stewarded by Ecuador and the Galapagos community. An important link in the “science to action” chain, bringing hidden and poorly appreciated ocean biodiversity to life in ways we couldn’t have imagined just 15 years ago.