Author: Joshua Vela Fonseca

We can all support the science generation. Before graduating from Visual Arts I never thought I would be able to work alongside scientists in their field studies at the most pristine corners of the Galapagos Islands. But conservation could start with our every-day habits at home and end up becoming our career without realizing it. At the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF) I found a place where I can contribute as an artist to the fight for a sustainable world. In 2020, I completed two years as a collaborator to the CDF Communication Department and in March the Galápagos Verde 2050 project gave me the opportunity to document and learn in a fieldwork to Baltra Island. With a bag, 3 cameras, and 5 lenses, I had more gear than clothing, and so I joined the GV2050 team during a five-day journey to help restoring the ecology of the island, and this is what I learned:

GV2050 in the Island of Baltra (South Seymour)

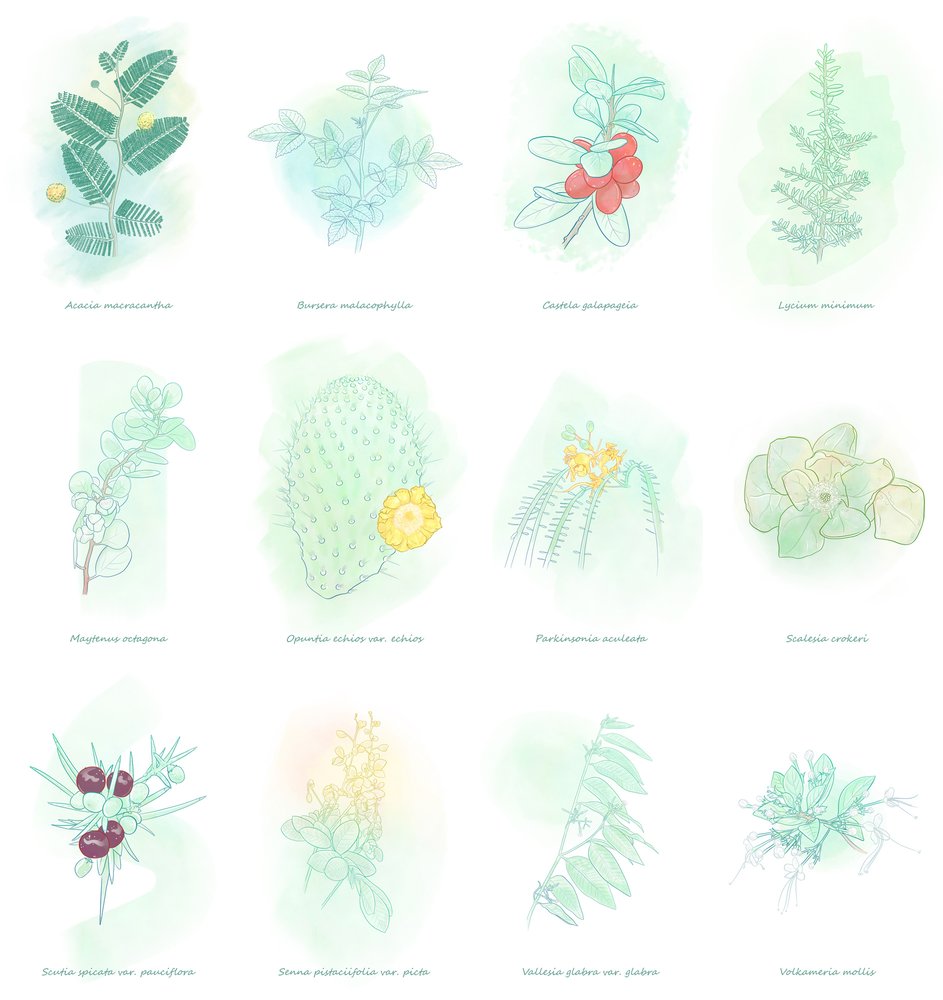

CDF started the Galápagos Verde 2050 project (GV2050) in 2014. It works with the ecological restoration of degraded ecosystems, and sustainable agriculture practices by using three water-saving technologies: Groasis, Cocoon, and Hydrogel (Jaramillo, 2015). Since then, the GV2050 project has conducted activities on the island of Baltra with a restoration program around the most damaged sectors (figure 1). Along these six years, the work being conducted included the planting of twelve different species in eight sites and total of 5,607 plants that have been brought to Baltra. This is a work that demands time, patience, dedication, and interdisciplinary collaboration.

The fieldwork that GV2050 does

“As the hustle and bustle of everyday human life has been put on hold across the world, due to the effects of COVID-19, nature is popping up in unexpected areas that are usually overrun by humans. This is Galapagos Verde’s wish for Baltra Island. That the area once destroyed by human war can be once again flourishing with native and endemic species.” -Esme Plunkett, 2020

As the land iguanas come out to sunbath during the first rays of the morning (figure 2), so does the GV2050 team to start their work in the ecological restoration of Baltra. The fieldwork, during this trip, took place at "Casa del Ojo" and "Parque Eólico": two of their six study sites in this island.

Along the five days of duration of this field trip, more than 300 new plant individuals of ecologically key species (figure 3, 4) were planted in these sites, by using water-saving technologies. Though, throughout the entire fieldwork, there is much more work involved beyond planting. In fact, a lot of effort is put at carrying water, installing the water saving technologies, and controlling growing rates of previously planted individuals.

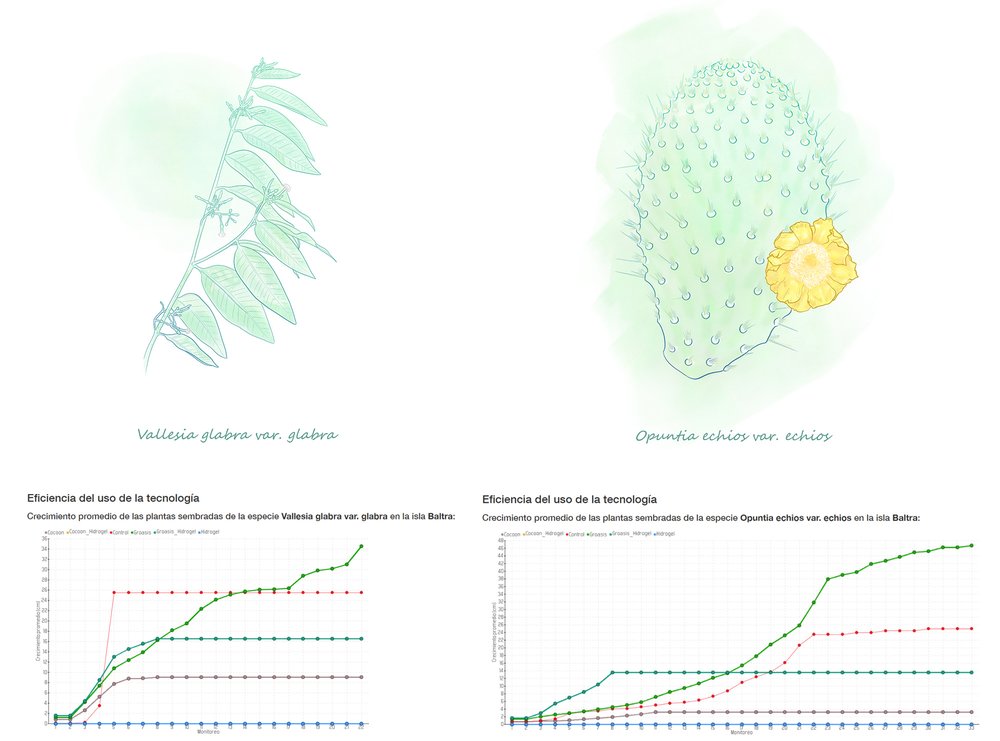

The project aims to understand how each specie does grow in response to the different technologies associated to their planting. These little plants came from seeds collected from the field that were afterwards germinated in a laboratory. They were raised, cared, controlled, and monitored in the GNPD´s forest nursery, until they are finally brought to the different islands where the project take place. After the planting, monitoring activities, conducted every three months are essential for the study. Ecological and biological data is collected and analyzed to better understand how the restauration process is being addressed, especially from key species for the Galapagos ecosystems such as the Opuntia (Tapia et. al., 2019; Jaramillo et al., 2020).

The worksites are key points for future plants to fulfill their ecological role and eventually spread throughout Baltra by natural means. This idea flashed through my head for the five days we worked there as I watched the team focusing on studying and preparing the ground, planting, setting the technology devices, watering and identifying the plants, and protecting them with a mesh. The work of each GV2050 team member (past, current, and future) will undoubtedly multiply, as a long-term investment for sustainability.

The sunset marks the end of the workday as well as the hustle of the nearby airport. The Cocoons and Groasis are stored, the hydrogel is prepared for the following day, and materials are collected. On our way back to the Air Force’s military base, the iguanas soak in the last sunrays as they watch us pass by. Little do they know; the project work will continue for another 30 years.

After my work with the GV2050, I can personally say that I needed a couple of diclofenac sodium injections to soothe my muscles – and that is after just one trip with the project! However, the team’s sacrifice comes with satisfaction of an ever-closer goal to know how Galapagos could be in 2050. It is gratifying to know there are initiatives that work to imagine a better future for the Galapagos, a common objective across all the projects of the Charles Darwin Foundation. This field trip is one of many, but it is an example of what we need for the well-being of the islands.

We would like to extend our gratitude to the Ecuadorian Air Force (FAE), the Ecuadorian Navy, ECOGAL, public and private institutions, especially the COmON Foundation and the Galapagos National Park Directorate, that make the work of Galápagos Verde 2050 in Baltra possible.

I would also like to thank the editors of this blog: María José Barragán, Patricia Jaramillo Díaz, Isabel Grijalva, María Guerrero, Esme Plunkett, and Andrés Cruz.

References

Cayot, L.J., Menoscal, R., 1992. Land iguanas return to Baltra. NOTICIAS DE GALAPAGOS No 51, 11-13.

Gibbs, J., 2013. Restoring Isla Baltra’s Terrestrial Ecosystems: A Prospectus. 1-19.

Jaramillo, P., Tapia, W., Gibbs, J., 2017. Action Plan for the Ecological Restoration of Baltra and Plaza Sur Islands. 2, 1-29.

Jaramillo, P., Tapia, W., Negoita, L., Plunkett, E., Guerrero, M., Mayorga, P., & Gibbs, J. 2020. The Galapagos Verde 2050 Project (Volume 1). Charles Darwin Research Station, Puerto Ayora, Galapagos.

Jaramillo, P. (2015). Water-saving technology: the key to sustainable agriculture and horticulture in Galapagos to BESS Forest Club.

Ministerio del Ambiente, 2019. Informe Anual de Visitantes. Ministerio del Ambiente. Galápagos.

Tapia, P., Negoita, L., Gibbs, J., & Jaramillo, P. (2019). Effectiveness of water-saving technologies during early stages of restoration of endemic Opuntia cacti in the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador. PeerJ Life & Environment, 1-19. doi: https://peerj.com/articles/8156/

Sulloway, F.J., Noonan, K.M., 2015. Opuntia Cactus Loss in the Galapagos Islands, 1957-2014 (Pérdida de cactus Opuntia en las Islas Galápagos, 1957-2014). Puerto Ayora.

Toulkeridis, T., Angermeyer, H., 2019. Volcanoes of the Galápagos. 214-225.

Woram, J.M., 2018 Galápagos History & Cartography. Retrieved on April 12, 2020, de http://www.galapagos.to/

Woram, J.M., 1992. That first iguana transfer. Noticias de Galápagos No 51, 20-22.