Turtles and tortoises are the most imperiled group of back-boned animals with over 60% of the 356 known species threatened with extinction. The giant tortoises of the Galapagos are no exception: “Of the 15 species of Galapagos tortoises, three species (20%) are vulnerable, three species (20%) are endangered, six species (40%) are critically endangered, and three species (20%) were driven to extinction in modern times.

Ectothermic animals (‘ecto-’ meaning outside, ‘-therm’ meaning heat or temperature)—such as most insects, fishes, amphibians, and reptiles—are unable to regulate their body temperature through heat generation as do mammals and birds. Instead, ectothermic animals rely on environmental temperatures to regulate their internal temperature. For example, terrestrial species seek shade when they are too hot and bask in sunlight when they are too cold. Their internal body temperature controls the rate of metabolism, regulating bodily functions such as movement, digestion, growth, and reproduction.

All crocodilians, some lizards, and most turtle species rely on temperature in another interesting way: offspring sex is determined by temperature, a phenomenon known as temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD). In Galapagos giant tortoises, female offspring are produced at warmer temperatures and male offspring are produced at cooler temperatures during a critical period of egg incubation. The relative number of females and males (sex ratio) is an important ‘vital rate’ for the study of populations and informing conservation.

The Galapagos Tortoise Movement Ecology Program investigated the roles of nest location and temperature in influencing the sex of hatchling tortoises. The findings from this study offer important information for the conservation of giant tortoises, among other species with TSD, in our changing world.

Galapagos giant tortoises cover a lot of ground during their migration, but they nest in specific locations. On Santa Cruz Island, three nesting zones were identified that spanned a range of elevation. When nests were found, nest cavities were carefully opened to place a miniature temperature sensor among the eggs, then the nests were closed to continue their natural incubation. Additionally, hatchling and juvenile tortoises in the nesting zones were inspected using veterinary tools to determine their sex.

“Combining advanced veterinary and ecological techniques that allowed us to determine both egg incubation temperatures and juvenile sex was key for gathering these data, which provide insights on tortoise conservation during a period of rapid changing climate,” said lead author Sharon Deem, a wildlife veterinarian, epidemiologist, and Director of the Saint Louis Zoo Institute for Conservation Medicine.

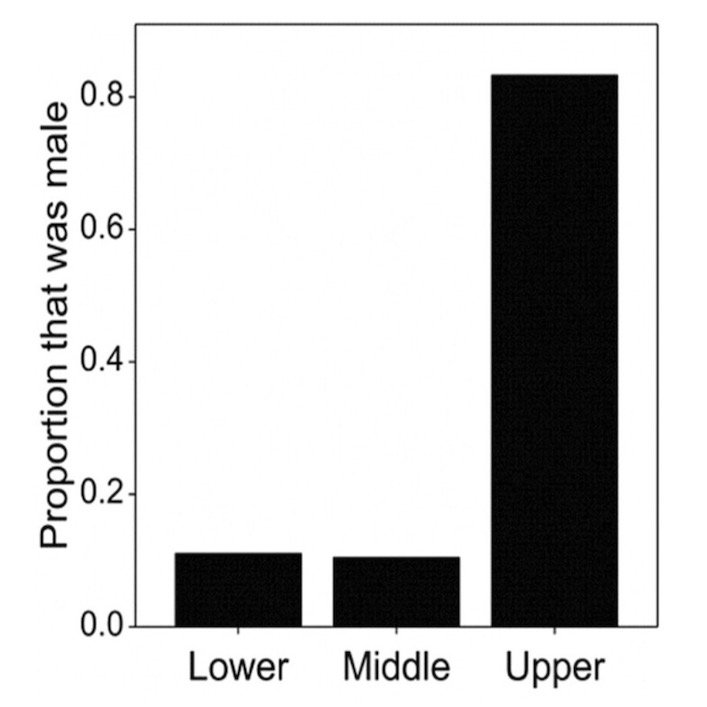

Findings from this study were very exciting! During the critical period of sex determination, nest temperatures were much warmer in low and middle elevation nests, but cooler in the high elevation nests. In the warmer lower and middle elevation nesting zones, approximately 90% of juvenile tortoises were females. In contrast, in the cooler higher elevation nesting zone, 80% of juvenile tortoises were males. Small increases in elevation (of approximately 50–100 metres) resulted in cooler nest temperatures (by about 1.6°C) and a dramatic flip from strongly female-biased sex ratios at lower elevations to a strongly male-biased sex ratio at the highest elevation!

This study was motivated by uncertainty of how a changing climate might impact giant tortoise sex ratios, and the potential consequences for tortoise populations and their conservation. Warming temperatures of 1–4°C, as are predicted for Galapagos, could change many aspects of tortoise reproduction: nesting habitat availability; nest conditions, such as temperature, precipitation, and surrounding vegetation; and nest outcomes, such as hatching success and sex ratios.

“Before this study, we knew nothing about sex ratios of hatchling tortoises in the wild and had no concrete data on how a changing climate may impact them in the future. Our study provides the first data on the impact of nest incubation temperature on the sex ratios of free-living Galapagos tortoises,” said Deem.

Stephen Blake, study co-author and professor at St. Louis University, added, “We showed the extreme sensitivity of hatchling sex ratios to nest temperatures in the wild. Monitoring sex ratios of populations most vulnerable to climate change may be important in guiding conservation actions, such as temperature-controlled incubation to optimize future sex ratios.”

Learn more about ongoing research involving giant tortoise reproduction in the video below and by visiting our program page and Youtube.

This research was led by the Charles Darwin Foundation, with the support of the Saint Louis Zoo Institute for Conservation Medicine, the Galapagos Conservation Trust, Houston Zoo, The Swiss Friends of Galapagos, the National Geographic Society Committee for Research and Exploration, the National Science Foundation, and the Galapagos National Park Directorate. The Galapagos Tortoise Movement Ecology Program, together with other projects at the Charles Darwin Foundation, depend on the generosity of our donors. Please donate today .

This publication is contribution number 2487 of the Charles Darwin Foundation for the Galapagos Islands:

Deem SL, S Rivera, A Nieto-Claudin, E Emmel, F Cabrera, S Blake. 2023. Temperature along an elevation gradient determine Galapagos tortoise sex ratios. Ecology and Evolution 13: e10008.