Over the past decade conducting applied research towards the conservation of sharks in the Galapagos Islands, the Charles Darwin Foundation Shark Ecology research team has mainly focused on species that, sooner or later during their busy sharky lives, tend to hang out near the coast. Our research, conducted in partnership with the Galapagos National Park Directorate and several national and international collaborators, has been investigating species such as the scalloped hammerhead, tiger, Galapagos, blacktip, silky and even whale sharks. These are species that frequently visit the coasts of the Galapagos Marine Reserve to go about their normal sharky business: enjoying green turtle sashimi (such as tiger sharks predating on green turtles); stopping-by the local spa (like scalloped hammerhead sharks scratching their claspers); or just making a quick pit stop before heading into a casual 16,000 km stroll right into the middle of the Pacific (like our ‘record-breaker ’ silky shark).

Oceanic sharks are in serious trouble

More recently, in partnership with the Guy Harvey Research Institute and the Save Our Seas Foundation Shark research center at Nova Southeastern University, we have ventured ‘into the blue’ to gain a better understanding of the life of a true ocean wanderer: the blue shark (Prionace glauca). The blue shark is one of the most heavily fished shark species globally, and among the top three most frequently captured sharks in Ecuadorian waters . Despite being classified as near-threatened by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), very little is known about the most basic life history of the blue shark in the Tropical Eastern Pacific.

This new project seeks to shine some light on this species' movement patterns, and see where it likes to ‘hang out’ during different times of the year. This information will be key to identify areas of overlap with the numerous artisanal and industrial fishing fleets that operate in this part of the world, which in turn will serve to inform management actions aimed at reverting ongoing population declines. The project will also provide information about how much protection the Galapagos Marine Reserve, and other large marine protected areas in the region like the recently-created Hermandad Marine Reserve, are providing to these oceanic sharks.

Easier said than done...

Deploying satellite tags on coastal shark species is kind of an ‘easy-science’. It normally takes place during daylight hours, allowing the research team to sleep in the comfort of a warm bed after a long day at sea. For some species like the scalloped hammerhead, we simply free-dive to attach satellite tags on them during their seasonal aggregations in shallow waters. But oceanic species such as the blue shark are an entirely different story as they tend to be more active at night.

Nighttime is when scientific fishing to safely capture these ocean wanderers has to happen - all the way until sunrise! These sleepless nights are intended to maximize the chances of safely capturing sharks quickly, allowing us to tag and release the animals with as little stress as possible, thereby also maximizing the limited ship time our research team has with funding constraints.

Great success!

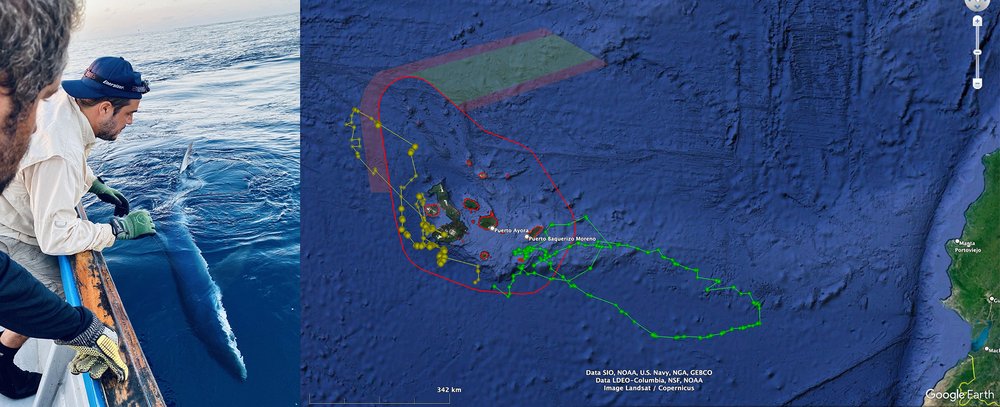

Thanks to the local knowledge of our collaborating Galapagos artisanal fishers that placed us right on ‘blue-shark-central'; together with the ‘Spartan’ commitment of the sleepless shark tagging team, our first two-night venture into the blue yielded a set of six tagged blue sharks!

Now, thanks to the satellite transmitters deployed on the sharks’ dorsal fins, we can monitor their whereabouts almost in real time. Over the next few months we will be conducting similar nocturnal missions into the blue with the aim of deploying up to 50 satellite tags on blue sharks so we can collect meaningful data of their movements that can be used by policy makers to inform policies designed to revert ongoing population declines.

We are very grateful to the Save Our Seas Foundation, Focused on Nature Foundation, the Mark and Rachel Rohr Foundation, and the Darwin and Wolf Conservation Fund for their support in making this study possible.