Silent invaders in the Galapagos Marine Reserve! A story of how we study them, through the COVID-19 pandemic

Author: Patricia Isabela Tapia

Introduced species represent the most important driver of biodiversity loss for oceanic islands (Brook, Sodhi and Bradshaw, 2008). Indeed, invasive species are the main threat for the ecological integrity of the unique marine and terrestrial ecosystems of the Galapagos (DPNG, 2014). We, the Marine Invasive Species Programme led by Dr Inti Keith, carry out research on marine invasive species, for their prevention, detection and management in the Galapagos Marine Reserve (GMR). We mainly focus on the fouling (encrusting) community on artificial habitats (like harbors). These artificial habitats serve as a model system, as these are hotspots for biological invasions worldwide, mainly due to marine traffic (Ruiz et al., 2009). So, as part of our usual activities, in January 2020 we started monitoring benthic invertebrates (organisms that live on the ocean floor and have no backbone) in one of the most heavily used harbors of the Galapagos: Seymour Port on Baltra Island. Our aim was to passively collect benthic invertebrates present on this study site to detect marine invasive species, allowing a rapid response to possible marine invasions in the GMR.

Week 0

It’s a sunny and beautiful morning in the Galapagos. We are ready to depart from Puerto Ayora, Santa Cruz Island to Baltra Island, for some fieldwork. We are about to deploy 32 PVC (polyvinyl chloride) settlement plates, hanging them from the dock at Seymour Port, one meter underwater and parallel to the seafloor. In this way, we pretend to mimic floating docks, and observe what species adhere and grow on them.

It seems like another day in our job. Though for me, it is a day with the extraordinary opportunity to be part of world-class scientific research in the first Natural World Heritage Site ever declared by the UNESCO, the cradle of Darwin's thinking on biological evolution, and the place I have the privilege to call home.

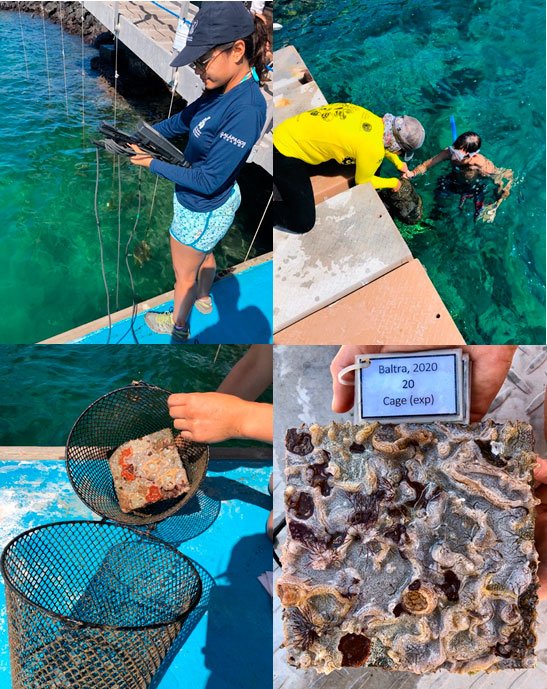

We successfully deployed the 32 settlement plates, the treatments consisted of: controls (plates attached to bricks only), half cages (assembled plates with top cage only) and full cages (assembled plates with full cage). We planned to leave our plates there for 12 weeks and return every two weeks to monitor them, taking photographs, recording the presence of any animal and plant on them as well as oceanographic data at the study site. Little did we know that the world was about to stop and that we all had to hide from an invisible enemy: COVID-19.

Week 2

I don’t know what exactly we are going to encounter. To be honest, this job has been a learning journey. I am not a marine biologist, I am a general biologist, so fieldwork in the ocean as opposed to my mostly-terrestrial experience, is still a bit challenging, but I absolutely love sharing “the office” with sea lions, sharks, colorful fish and many other smaller forms of life that have always been there, but that we usually ignore: the fascinating sessile organisms (encrusted to a substrate and cannot move about freely).

Unlike charismatic species like sea lions and marine birds, sessile organisms are much less popular. Perhaps their smaller size and inability to move make them less attractive? I believe these are captivating creatures and that they make the ocean even more interesting and full of life, we just have to pay more attention. Maybe in the photographs of following weeks you will see what I mean.

Observing the presence of living organisms already attached to our plates after only two weeks, not only is exciting but it also provides information on their life cycles! The only thing I am thinking now is I can’t wait to see how these plates look like on week 12.

Week 4

It’s a sunny day, the water temperature of the sea is above 26°C, thus staying in the water for several hours is indeed enjoyable. As soon as we arrive to our study site, we see that our plates are much fuller of life!

Plate 20 (full cage) shows visible growth of many animals (yes, what you are observing on these plates are animals!), particularly the white colonial sea squirt (Didemnum perlucidum) dominating the plate. This is an invasive species in Galapagos and is considered a marine pest on many other places (Carlton, Keith and Ruiz, 2019; Lambert, 2019).

Plate 7 (control) shows less animal-plant presence, probably due to predation in the absence of a cage. Other controls and half cages on occasions even present clear predation traces.

Week 6

Its March 12, just a day after the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak a global pandemic. Just a few days before reporting our first COVID-19 cases in the Galapagos, we are able to travel to Seymour Port, Baltra Island and monitor our plates for the last time.

After six weeks of deployment, plate 2 (full cage) shows visible progressive growth of sessile organisms. The presence of the following animals stands out: the invasive ascidians Didemnum perlucidum (white colonial sea squirt), Botrylloides niger (orange colonial sea squirt) and the invasive bryozoan Bugula neritina (purplish-brown bushy “moss animal”). A similar pattern has been observed in most of our plates in full cages, which is concerning due to the highly invasive behavior that these three species present in the Galapagos and worldwide. In fact, these are within the most notable introduced biofouling species currently present in the Galapagos (Carlton, Keith and Ruiz, 2019), which without doubt has important implications for conservation and management decision-making in the GMR.

The visual difference in plant and animal growth on plates 19 (half cage) and 26 (control) compared to full cage plates is evident, which again is most likely explained by predation. Plates 19 and 26 just like many other half cages and controls show traces of predation, which are likely left by fish. We have observed small and big fish-eating organisms living on the dock’s lateral and lower surfaces, some even feeding with most of their bodies outside of the water to reach such organisms.

Nobody thought that the world would suddenly have to stop for so long. Unexpectedly, we had to hide from a novel virus and leave our experiment halfway… I hope that the new world we are building during this crisis is less indifferent to the suffering of others, including nature. I hope we can all make better choices and change our lifestyles to more sustainable ones, so that one day, we don’t have to worry about some silent invaders taking over our seas or any species being taken out from their home ranges. Let’s survive this pandemic, healing ourselves and the planet. This might be our last chance to make things right.

I am afraid we didn’t make it to week 12 of our experiment. Our plates have been hanging from the dock at Seymour Port for 47 weeks now. However, we will use all samples to learn more about biofouling species in the GMR and next year we will be ready to repeat our experiment, one more time.

This programme is possible thanks to the generous support of our donors: Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Galapagos Conservancy, Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic Fund, Galapagos Conservation Trust, Paul M. Angell Foundation and Ecoventura (current donors). You can read more about our work here. If you would like to contribute to the work of the Charles Darwin Foundation for the conservation and sustainability of the Galapagos Islands, please DONATE and/or share our work with your friends and family!

References

- Brook, B. W., Sodhi, N. S. and Bradshaw, C. J. A. (2008) ‘Synergies among extinction drivers under global change’, Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 23, pp. 453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.03.011.

- Carlton, J. T., Keith, I. and Ruiz, G. M. (2019) ‘Assessing marine bioinvasions in the Galápagos Islands : implications for conservation biology and marine protected areas’, Aquatic Invasions, 14(1), pp. 1–20.

- DPNG (2014) Plan de manejo de las áreas protegidas de Galápagos para el buen vivir. Edited by A. Izurieta et al. Puerto Ayora, Galápagos, Ecuador: Imprenta Mariscal. doi: 10.1590/S0004-282X2003000500014.

- Lambert, G. (2019) ‘Fouling ascidians (Chordata : Ascidiacea) of the Galápagos : Santa Cruz and Baltra Islands’, Aquatic Invasions, 14(1), pp. 132–149.

- Ruiz, G. M. et al. (2009) ‘Habitat distribution and heterogeneity in marine invasion dynamics: the importance of hard substrate and artificial structure’, in Wahl, M. (ed.) Marine Hard Bottom Communities, Ecological Studies (Analysis and Synthesis). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 321–332. doi: 10.1007/b76710_23.