Authors: Samara Zeas y Paz Guillén Liger, thesis students

In mid-2020, we found ourselves in the last year of our biology studies, thinking about our thesis. At the time, we both had a clear goal: to combine fieldwork with laboratory work. We considered several possibilities, some clearer than others. After several weeks of exchanging emails and frequent meetings, we decided to work with one of the most emblematic species of our country, the Galapagos Giant Tortoises.

Our research is a collaboration agreement between the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF) and the University of Azuay (UDA), and it is part of the health component of the Galapagos Tortoise Movement Ecology Program (GTMEP). In early July 2021, and with the support of Ainoa Nieto Claudín (CDF) and Rodrigo Caroca (UDA), we set off!

Our project in Galapagos is focused on studying one of two species of giant tortoises that reside on Santa Cruz Island, namely Chelonoidis porteri, a species that inhabits the west of the island. We found that many of these reptiles presented a yet unexplained whitish erosive lesion (appearing like white marks) on their carapace. Based on this observation, our work aimed to characterize the microorganism which caused these white lesions using molecular biology and microbiology tools.

Because this is a relatively new field of research, we had to contemplate several methods to carry out our test, which meant we had to prioritize laboratory equipment over personal items when packing our bags. Once on the island and as the days passed, we began to gradually adapt to the pace of work, and, by mid-July, we had experimental tests of the methodology and our first field trips to collect samples.

In the field, we were very fortunate to be able to see the tortoises in their natural habitat. Something we loved is that no matter how many times we go in the field, there is always something new to discover; while it is true that tortoises are "big" animals, seeing a hatchling makes you realize how fragile wildlife can be.

As we collected the shell scrapings, to be processed in the laboratory, one becomes creative, and Galapagos makes you even more creative because you have to make good use of the available resources. Experimenting is undoubtedly an important part of science, depending on our objectives and with some patience, we improved the steps.

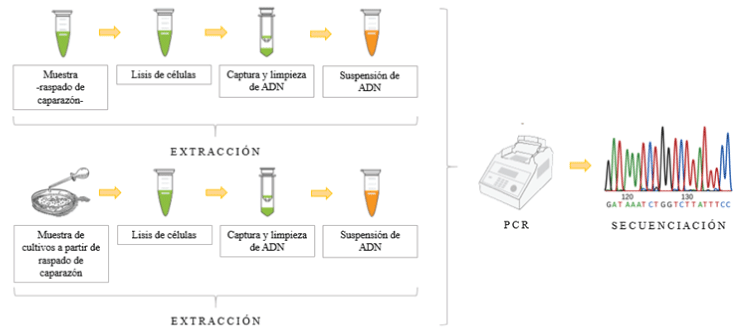

Back in the laboratory, the first step of the methodology is to extract the genetic material (DNA). This consisted in testing various methods or protocols that would allow us to obtain good quality samples from the shell scrapings, using molecular biology and microbiology techniques. This was done to obtain a DNA sample that preserves its integrity, making it as free of contaminates as possible for analysis.

After several attempts, we managed to find an efficient extraction protocol that led us to the next step: processing the obtained samples in a PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction). This step is very important because it allows us to study the DNA molecule in greater detail.

Next, we perform a purification of the samples. This allow us to eliminate a large number of contaminants (proteins, enzymes, detergents, salts, and lipids) that can alter the results of the research, and helps us to preserve the quality of the DNA samples.

We cultured the microorganisms collected from the shell scrapings in petri dishes, mainly to identify fungi and bacteria. This allowed us to know the growth conditions or preferences of these microorganisms. During this growth stage, what started as a "simple experiment" turned into a very time-consuming process: we had to identify more than 11 colonies among fungi and bacteria, differentiating their shapes, colors, textures, and even their most minuscule structures, which after staining revealed the shape, the way they group the structure of the cells, and their size.

The molecular and microbiological results show 8 genera and 7 species of microorganisms, including fungi and bacteria. In both the white-spotted shell and the healthy shell, the isolated microorganisms correspond to the environment in which the giant tortoises live, with the exception of Aphanoascella galapagosensis, which is present in 66.7% of the whitish shells and missing in the healthy shell. In other words, the fungus A. galapagosensis is the main cause of white spots on the carapace of Santa Cruz tortoises (C. porteri). This information is part of the first baseline of microorganisms present on the shell of Galapagos tortoises.

This experience has been profoundly rewarding and we are eternally grateful for everyone that helped us with our project. We hope to return soon and support research for the conservation of the Galapagos.

References